One of the most highly-anticipated movies of the year is finally in theaters, as Killers of the Flower Moon exposes, once again, the massive gaps in the U.S. educational system.

The same conversation was prompted by the release of HBO’s Watchmen series, which served as many Americans’ first-ever introduction to the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. Our educational institutions are failing us, time and again, and that point is being driven home once again with the release of Martin Scorsese’s examination of a series of murders during the 1910-30s. Those murders are a real part of history, as are the characters that headline the new film.

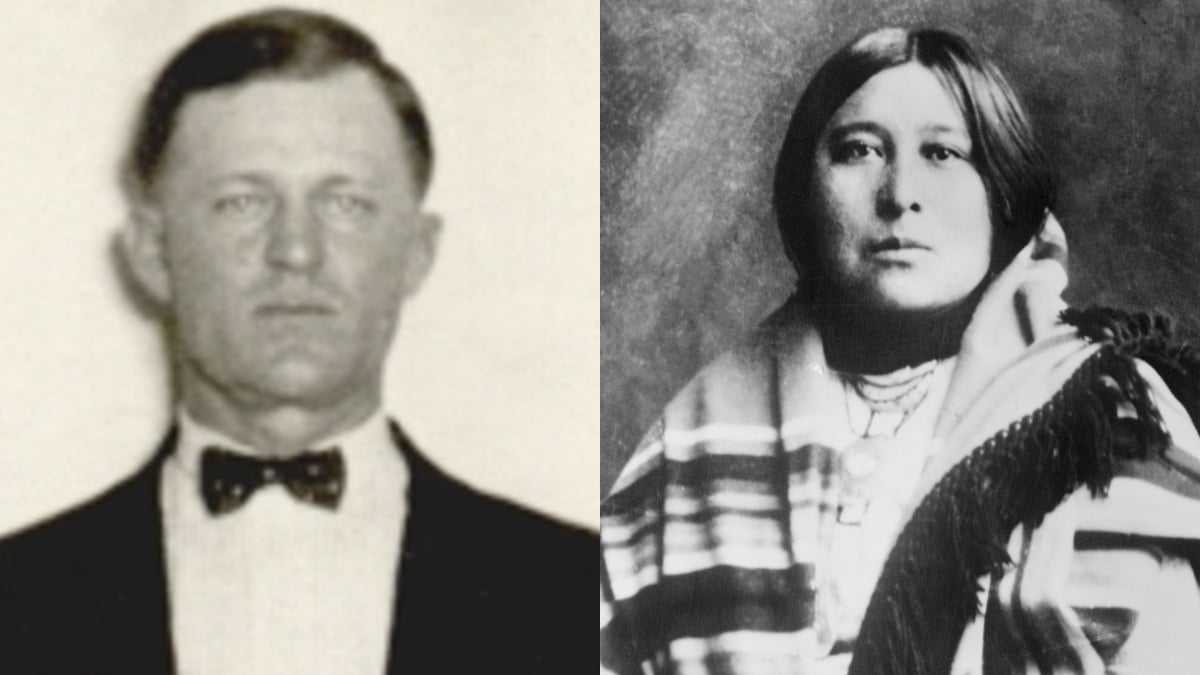

Did Ernest and Mollie Burkhart exist in the real world?

Many of the leading characters in Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon are, in fact, based on people from the real world. Ernest and Mollie Burkhart — originally Mollie Kyle — met in Oklahoma in the 1910s. Ernest moved to the area in 1912, along with his brother, in search of jobs in the oil industry. He lived with his uncle, William Hale, a business owner and cattleman in the area. He met Mollie while he was working odd jobs, including as a taxi driver, and began the process of courting her. A few years later, in 1917, they married.

Mollie, meanwhile, was a young woman and member of one of the most wealthy — and envied — groups in the United States. She was a citizen of the Osage Nation, which — thanks to some brilliant decisions — maneuvered itself into hefty oil money. The purchase of land in Indian Territory, which became the U.S. state of Oklahoma, led the Osage to become some of the wealthiest people in the entire country, and thus targets of greedy white men.

One of the most predatory of these white men was Hale, and by extension, Ernest. Ernest’s marriage to Mollie was driven in large part by a desire to get in on the oil money, and to maneuver more white people into positions of influence in the Osage Nation. See, all that oil-based wealth — which numbered in the tens of millions — was divided among Osage Nation citizens, using a system called “headrights.”

These headrights allowed money to be distributed equally among the tribe’s more than 2,200 members, but came with a catch that Hale and Ernest quickly worked to exploit. See, when a headright owner died, their headright was passed down to the next legal heir. That includes non-Osage heirs.

The Osage Murders, explained

With so much money flowing out of Osage land, it was only a matter of time before the government got involved. The government, convinced that Native people had no ability to manage such wealth, assigned greedy white “guardians” to the tribe, allowing them to gradually leech money from its rightful owners.

Soon after, the murders began. Osage started dropping left and right, some from mysterious causes, some from gunshot wounds and even explosions. As each one died, their headright was passed down — and not always to Osage heirs. In four years alone, between 1921 and 1925, more than 60 murders occurred in Osage County, almost all of them inexplicable and mysterious, and all connected to headright holders. The murdered Osage’s estates were passed down from person to person, winnowing the Nation’s wealth more and more over the years.

Eventually, the culprits behind the series of heartbreaking murders were uncovered, after the early FBI was tapped to investigate. Among the perpetrators were Hale and Ernest, who was linked to several of the murders and at least one attempt on Mollie’s life. Mollie survived and, in 1926, Ernest was sentenced to life in prison.

That sentence didn’t stick, unfortunately, but Mollie — despite being largely shunned by other Osage, due to her initial support of her husband — divorced him and later married John Cobb. Her children with Ernest eventually inherited their family money, but it was severely reduced during the Great Depression, leaving them with meager payouts in the decades following.

Ernest was pardoned two separate times, ultimately serving around ten years during his first sentence and nearly 15 a few years later, after his parole was revoked due to the robbery of his sister-in-law, Lillie Morrell Burkhart. He was released from his second sentence early as well, walking away from prison in 1966. Mollie passed away in 1937. She was only 50 years old.