“I’m gonna kill Aquaman and destroy everything he holds dear,” someone paid Emmy-winning actor Yahya Abdul-Mateen II to say in the trailer for Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom. “I’m going to murder his family,” he continues, “and burn his kingdom to ash,” which, even by supervillain standards, is ambitious. We’re talking about setting an underwater city on fire. It’s as alarmingly straightforward an introduction as you’re likely to get to Black Manta, the DC villain with the most legitimate claim to the title of “Aquaman’s nemesis.”

Dedicating your life to fighting a guy whose powers include “swims real good” and “needs a drastic visual overhaul to work on the big screen” isn’t for everybody — it takes dedication, perseverance, and above all, the sort of lack of self-awareness that usually leads to someone wearing a stupid hat. Enter David Milton Hyde, alias Black Manta, who wears a stupider hat than almost anyone not at the Met Gala.

And what compels him to disguise his face as an angry chrome Mento, scouring the seven seas in an attempt to sate his Aquaman-specific bloodlust? That’s a great question, and one that DC took a while to get around to answering.

Black Manta was introduced in 1967, and despite becoming a regular in both the comics and cartoons almost immediately, his history and motivations didn’t get a lot of love. There was a stunning reveal in the ‘70s where Black Manta took off his mask and revealed — brace yourselves — that he was Black, which I guess counted as a twist 50 years ago. He claimed to want to control the sea so that historically mistreated Black people could move there, which feels like the sort of thing you want to maybe let people vote on, but what do I know?

The many origins of Black Manta

The writers put off giving Black Manta a backstory until 1993, and once they started, they kind of couldn’t stop. His first tale of woe revealed that Black Manta started life as a kid who loved water, which is a solid enough jumping-off point. Then he was abducted by mean men on a boat, who forced him to do, you know, boat things. Terrible boat things. The experience, along with the fact that he tried to signal Aquaman to come and rescue him one time and Aquaman didn’t notice, made him hate water. What’s more, since he saw Aquaman as sort of the official spokesman for water, he decided to do whatever it took to murder the guy, the same way that people who get hit by a foul ball at a baseball game spend the rest of their lives trying to kill Mr. Met.

In 2003, the character got a gritty new origin story, this time as a boy with autism who was badly mistreated at Arkham Asylum. After an experimental treatment made him less autistic but more murder-happy, he grew up, built a custom submarine, made himself a helmet, hired an army, and took to the seas, the way anyone willing to pull themselves up by their bootstraps could if they’d just try hard enough.

The third time around, Black Manta got an origin that was a little more primetime-ready, swearing vengeance against Aquaman after the superhero inadvertently killed Manta’s father. It’s a lot closer to the version of the character that we see in 2018’s Aquaman.

What are Black Manta’s powers in Aquaman 2?

Aside from a zany stretch where he traded his soul to a demon in order to be transformed into a mantis/human hybrid fursona, Black Manta has traditionally gone about his day-to-day without a lick of superpowers. What abilities he does have, he developed on his own – an expert in hand-to-hand combat, he’s also come up with lots of his own gadgets, including his energy-blasting helmet and his artificial gills.

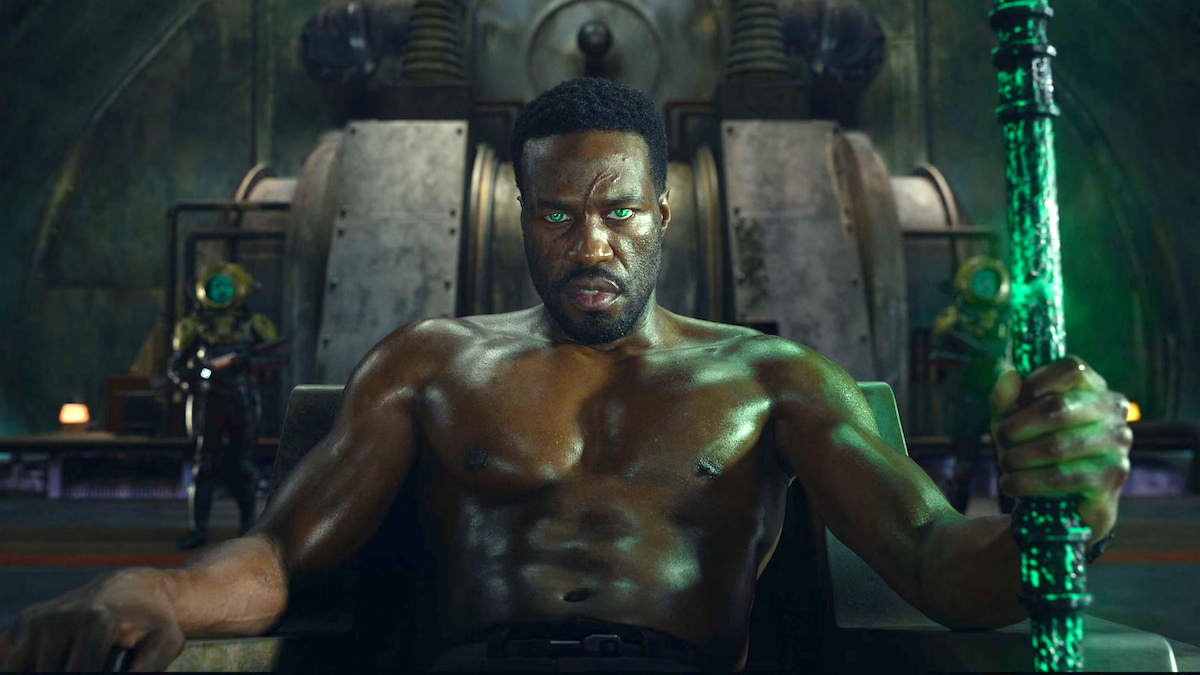

Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom seems to be adding a new power set into the mix, tossing Manta the Black Trident in one of those happy strokes of color coordination luck. The details on the Black Trident are slim at present, but it sure looks similar to the Black Lantern rings, from the Blackest Night storyline, bringing the dead back to life as nightmarish shambling monstrosities. It should be fun.

Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom theoretically hits U.S. theaters Dec. 20th, but, you know. Will it?