If you thought the recent American elections were the most contentious the country had ever seen, you’d be mistaken. For as long as the United States has existed, politicians and their supporters have been duking it out – figuratively and literally.

Of course, these political sparring matches leave many voters dissatisfied, as any Gore, Trump, or Sanders supporter will certainly tell you, but their pain is surely less than those felt in 1876. The bloody election lead to sweeping reforms and the secretive Compromise of 1877.

Post Civil War conflict sets the stage

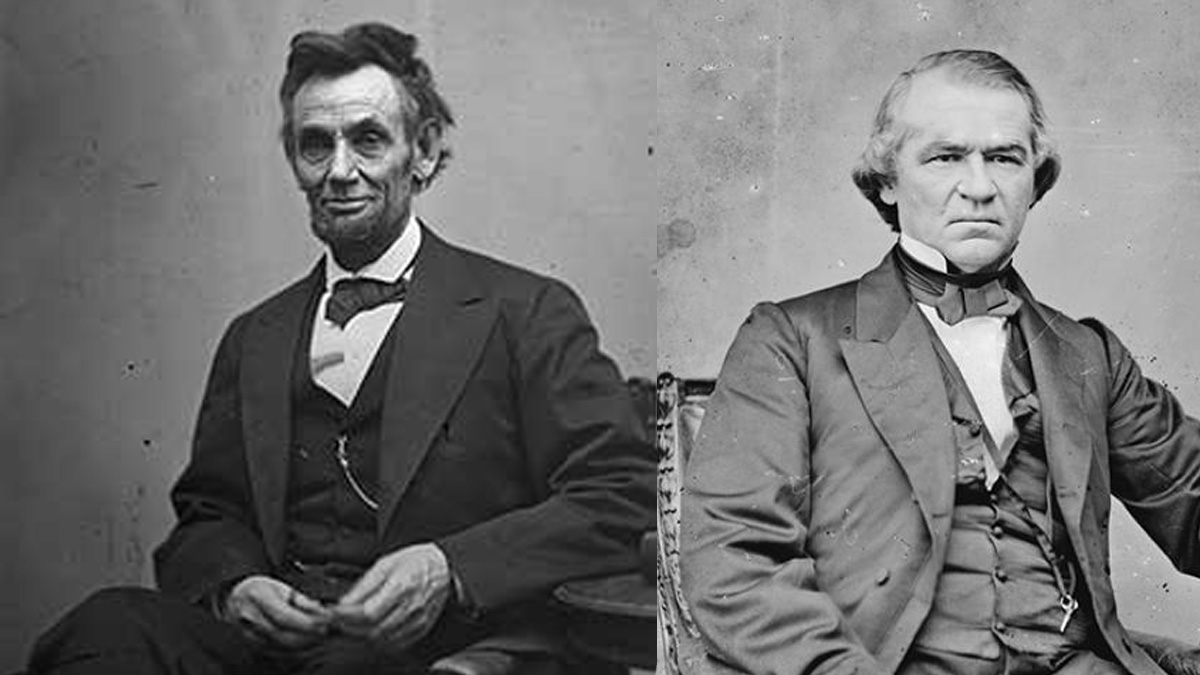

After the Civil War, reconstruction was a major conflict between the Republican and Democrat parties. Lincoln’s plan for reconstruction only required 10% of the population to swear loyalty to the Union, a number that many Republicans and Union supporters in Congress found to be unacceptable. After his assassination in 1965, his successor Andrew Johnson, was even more lenient.

Johnson moved for a speedy Restoration, believing that the Southern states had never truly left the Union. He thought that equal rights should be left to the individual states and that African American suffrage was a “distraction.” Part of this decision was driven by a fear that Freedmen would vote in “the wrong direction,” and that they were a serious threat to his potential election campaign in 1868, three years down the road.

Initially, Johnson’s Reconstruction was well received in the North, but the lenient rules soon rankled Northerners who began to feel as if the war had been fought for nothing. The Radical Republican faction, made up of staunch anti-slavery advocates, grew increasingly incensed that the South was not acknowledging its defeat, that slavery was still not fully ended, and that the lives of African Americans were not improving.

Southerners felt emboldened by the loose rules. They passed “Black Codes,” — slavery in everything but name — that forbade African Americans from leaving their positions on plantations and allowed law enforcement freedom to arrest Black people at will. One of the greatest pain points arose when prominent Confederate leaders were elected to Congress. When it assembled in December 1965, Northerners refused to seat the incoming Congressmen and demanded more aggressive Reconstruction legislation.

Johnson refused to speak on the continued rule of the antebellum elites (wealthy plantation owners who wielded most of the power) in the South, hoping that the Southern States would align with his reelection goals, and instead directed his attention to the vocal Radical Republican opposition. Over the next few years, Johnson infuriated both his Democrat allies and Republican moderates through indecisive legislation, consistent reneging on promises to help Freedmen, and his self-absorption. He lost an estimated 200,000 votes on George Washington’s birthday when he mentioned himself 200 times in an hour-long speech. Johnson lost control in 1866, when the Republicans wrestled control of Congress from the Democrats, at which point the Radical Republican faction enacted their plan for Radical Reconstruction.

Radical Reconstruction was essentially a military takeover of the South. It split the Southern states into 5 military districts –with the exception of Tennessee, which had already rejoined the Union. It required the Southern States to draft new constitutions that included universal male suffrage, as well as the ratification of the 14th Amendment – which granted citizenship equal civil and legal rights for former slaves and African Americans – a decision Johnson had left to individual states.

Johnson continued to hemorrhage support until he was impeached in 1867, becoming the first president to ever be unseated. He was replaced by Ulysses S. Grant, a Union hero and natural battlefield commander. Grants’ prowess as a general didn’t necessarily translate into presidential prestige, however. A military man at heart, Grant filled his cabinet with soldiers who saw nothing wrong with the militarized reconstruction shepherded in on the heels of his election.

The Election of 1876, the most contentious presidential election in America’s history

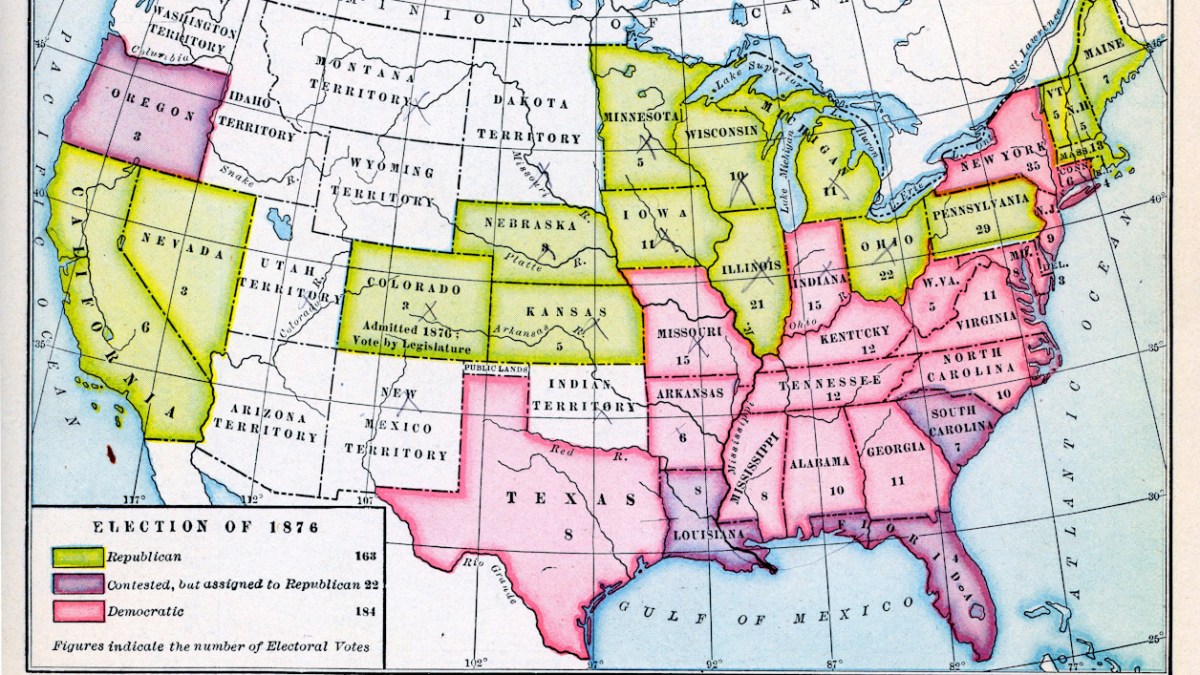

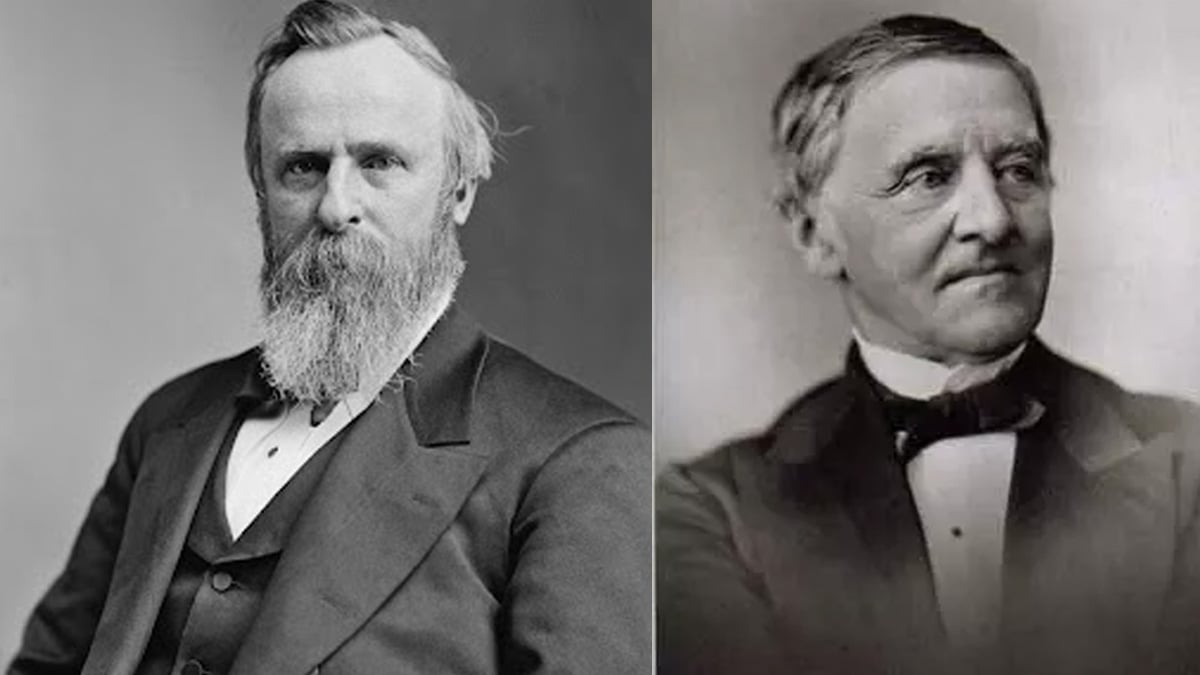

Grant served two terms in office before declining to run for a third. With so much bad blood brewing between the Republicans and the Democrats, the North and the South, the election was incredibly bitter. Rutherford B. Hayes (R) and Samuel J. Tilden (D) were the primary candidates, though Hayes was a compromise candidate after the frontrunner was unable to secure enough support at the Republican National Convention.

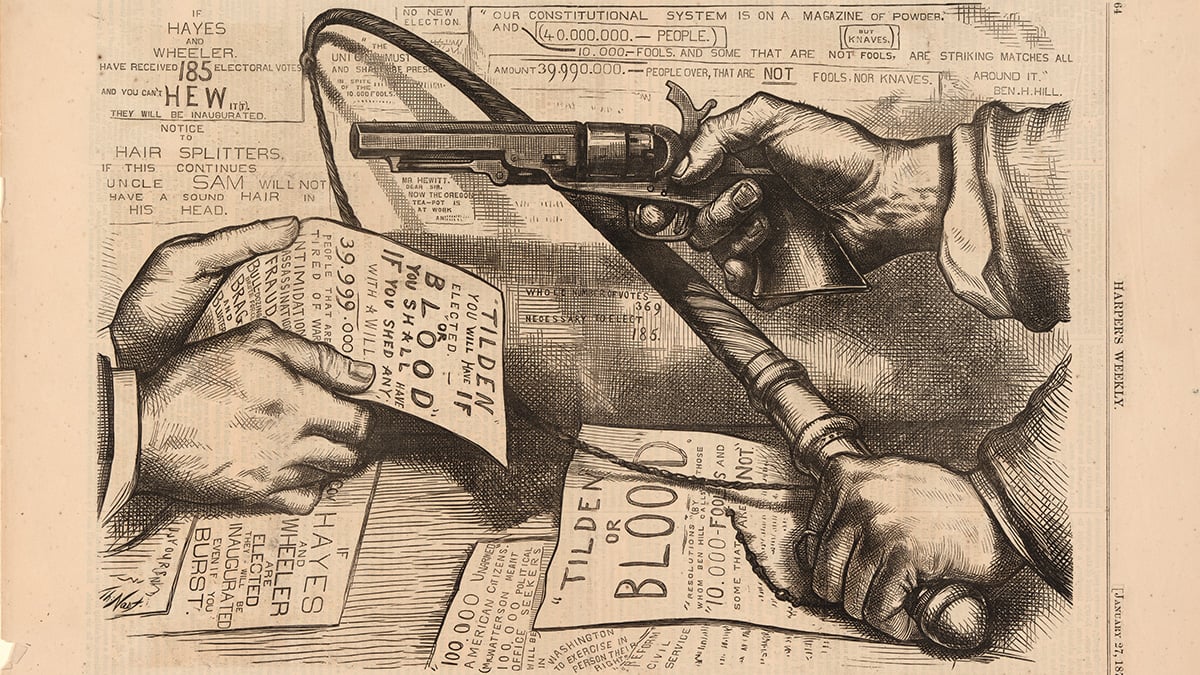

The election was fraught with allegations of electoral fraud, election violence, and disenfranchisement of Black Republicans. The Democrats relied on the White League and Red Shirts, para-military groups that violently disrupted rallies and suppressed both white and Black voters. In South Carolina, 101% of all eligible voters had cast their votes in a clear case of election fraud and an estimated 150 Black Republicans were murdered. Democrat ballots deceived illiterate voters by using the Republican symbol of Abraham Lincoln to steal votes. During the inevitable recounts, these votes were discarded.

Oregon battled bitterly, Hayes and Tilden were each declared the winner a respective two times in the state. Eventually, Hayes came out on top. Colorado, which had been admitted to the Union just one month before the election, helped swing the vote in Hayes’ favor after three rapidly-elected state legislators threw their lot behind him.

The intense back and forth was never ceasing, each party wanted to win, and the fighting reached Congress – the House of Representatives, which was controlled by the Democrats, and the Senate, which was controlled by the Republicans. With both bodies claiming it was their right to count the votes, the conflict had no end in sight. Facing a constitutional crisis, Congress passed a law to form the Electoral Commission, which would settle the dispute.

Five members from each house were selected and an additional four came from the Supreme Court. Those four voted on the 15th and final member, an independent judge – who was elected to the Senate and promptly left his post. In his stead, the Supreme Court had no recourse but to elect another Republican judge.

The Compromise of 1877

As the fighting continued, Inauguration Day was growing perilously close, and political tensions were at an all-time high. Nearly through months had passed, with neither side willing to compromise. Finally, during a closed-door meeting – of which there is no record – it was agreed that Hayes won the election by the second-closest margin in history (only 889 votes, just behind the 2000 election’s 537 vote margin).

Historians believe that the only reason Democrats agreed to Hayes’ victory was the monumental concession offered to the Southern States. Federal troops were withdrawn from the final two states under occupation (Louisiana and South Carolina), and Republicans agreed to a number of handouts, like Federal subsidies for a transcontinental railroad through the South (though this never manifested).

The kerfuffle, which was followed by two more close elections in 1880 and 1884, prompted Congress to pass the Electoral Count Act in 1887, which outlined detailed rules for the counting of electoral votes.

It would be just under 40 years before another Republican would win the vote in the formerly occupied Southern States. In the holdout states of Louisiana and South Carolina, it wasn’t until 1956, and 1964 respectively.

Having secured the popular vote by 3%, Tilden faded into obscurity after the election saying, “I can retire to public life with the consciousness that I shall receive from posterity the credit of having been elected to the highest position in the gift of the people, without any of the cares and responsibilities of the office.”