The history of The Constitutional Convention is one of debates, impasses, discussions, and compromises made in very stuffy rooms one hot Philadelphia summer in 1787 in what’s now known as Independence Hall.

It took nearly four months, over 100 days, for the convention to conclude and 39 out of the 55 present delegates to sign the Constitution, a document which is still, centuries later, integral to the lives of Americans.

Page Smith writes in The Constitution: A Documentary and Narrative History about the worldwide impact of the decision made by a few dozen men in Philadelphia:

“It is not perhaps going too far to say that Americans invented the modern notion of “a constitution. We will take note of the fact that constitutions of one kind or another have had a history extending back to classical times and earlier, but for all practical purposes, the modern constitution as a coherent written document, at least theoretically expressing the will of the people, was invented by American politicians in the summer of 1787.”

Page Smith (1978)

With the drafting of the Constitution, the U.S. government, with the structure we know today, would be formed. Although the Constitution has suffered necessary amendments since 1787, there is no understating the importance of this most famous document.

Before the Summer of 1787

Since 1781, there were talks among nationalists about rectifying the Articles of Confederation, adopted in 1777, and establishing a functioning government that would prevent states from taking advantage of one another. A series of riots by exasperated farmers, called Shays’ Rebellion, which began in 1786, further pushed the need for a reorganization of a strong federal government.

Before the Constitutional Convention, which began on May 25, 1787, there was a convention scheduled to be held in Annapolis, Maryland, in September 1786, with five delegates from each state supposed to attend. Only twelve in total were present. James Madison was there, Alexander Hamilton arrived later, and George Washington did not go. Most did not and the meeting was ostensibly a failure.

This lack of attendance was a reflection of the generalized reluctance of the states to join in on something that could end up curbing their capacity to manage their own business. In the end, seven states had no representatives at all. For three days, the few men present conversed and debated what they were there to discuss.

The nationalists among the group ended up turning the situation around by calling for a larger convention to be held in Philadelphia “to take into consideration the situation of the United States, to devise such further provisions as shall appear to them necessary to render the constitution of the Federal Government adequate to the exigencies of the Union.” (Christopher Collier, 1986)

The invitation to the convention was reportedly worded with careful vagueness so as not to startle those intent on maintaining the Articles of Confederation. This invitation was more tempting than the last due to Shays’ Rebellion, which made the need clear for a restructuring –or indeed complete overhaul – of the previous, weak state of government.

55 (Educated, White, Upper-class) Angry Men

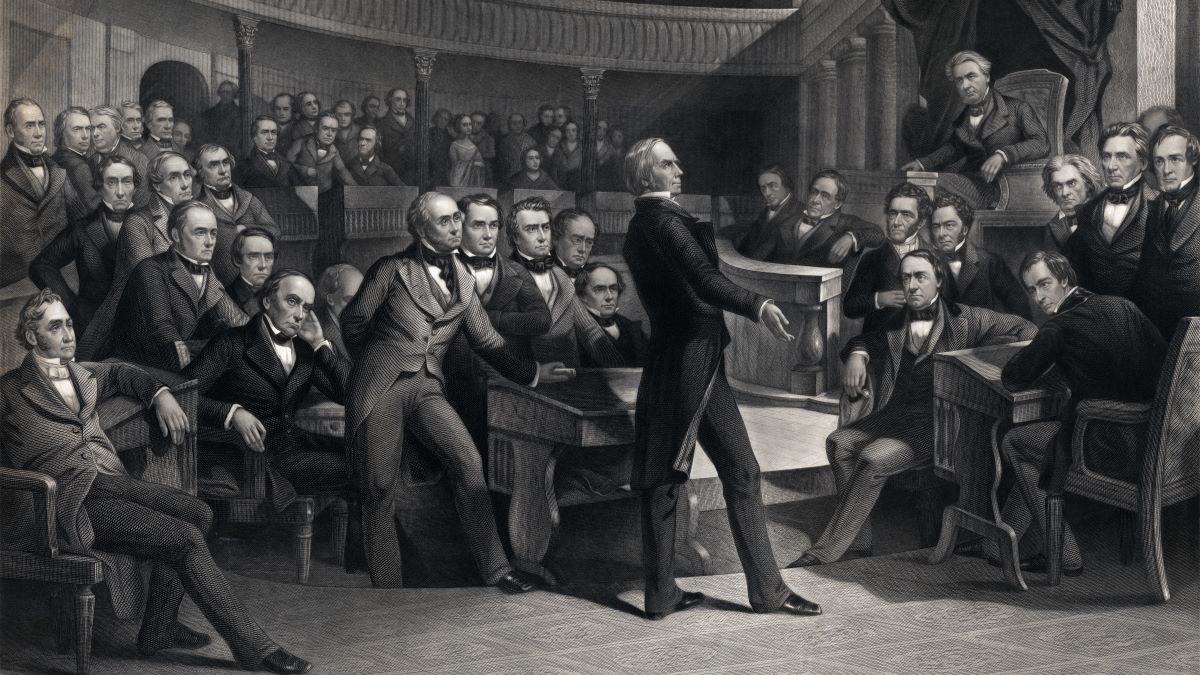

Twelve states appointed 74 delegates but only 55 showed up, with most being tardy. They kept arriving between late May and early June. Despite the monumental heat, the windows were kept closed to maintain secrecy, which Alexander Hamilton advocated for, and allow everyone to speak as freely as possible. In the debate room, state delegates were organized from south to north. Rhode Island was the only state not present. George Washington presided over the convention, unanimously elected by those present at the beginning of the Convention.

James Madison proposed the Virginia plan, which advocated for a strong central government divided into three branches which would internally check and balance one another. Debated from May 30 to June 13, it was opposed by the New Jersey plan, proposed by William Paterson, which wanted a unicameral instead of a bicameral legislature with equal representation.

In the end, Roger Sherman proposed the Connecticut Compromise which blended both plans, established a bicameral legislature with the House of Representatives based on population and the Senate with equal representation. This structure, agreed upon on July 16, consisted of two Houses, each representing one class of the social hierarchy, the aristocracy and the middle class. The Lower House would be elected by the people, and the Upper House would be elected by the Lower House.

It was in order to uphold democracy and prevent it from descending into pure anarchy that the delegates decided on a single executive branch with checks and balances involving the legislative and judicial branches. Hamilton, in particular, argued that Senators should serve for their lifetime, like the House of Lords in England, a system he very much admired. He also argued that the US should, like the British, have its own “king”, a chief executive that would be elected to serve the rest of his life and would bear the responsibility to veto or pass all federal laws. This idea was ultimately adapted by changing a lifelong monarch for a 4-year-term president, which the Electoral College would pick.

One of the main points of contention was the issue of slavery, with the Three-Fifths Compromise resulting from it. This meant that, for taxation and representation purposes, each enslaved person counted as three-fifths of a free individual. In terms of commerce, which was also a point of major debate, it was decided that Congress could regulate interstate and international trade, but a ban on the slave trade would not be permitted until after 1808.

On July 24, a Committee of Detail was appointed to draft the actual document of the Constitution based on the decisions made in the Convention. “Some of the loose ends that the Committee of Detail was charged with tying up were not only very loose, but touched on matters of considerable significance. The committee would be making decisions on very important questions. It was, in fact, to write a draft of a Constitution.” (Collier 1986) The final draft would be rewritten and polished to be as clear and straightforward as possible by the Committee of Style. The members of this committee were Hamilton, James Madison, Rufus King, Gouverneur Morris, and William Samuel Johnson.

On September 17 the final document was signed by 39 out of 55 of the delegates. Some refused to sign over the lack of a Bill of Rights, which would only come in the form of the first 10 amendments in 1791.