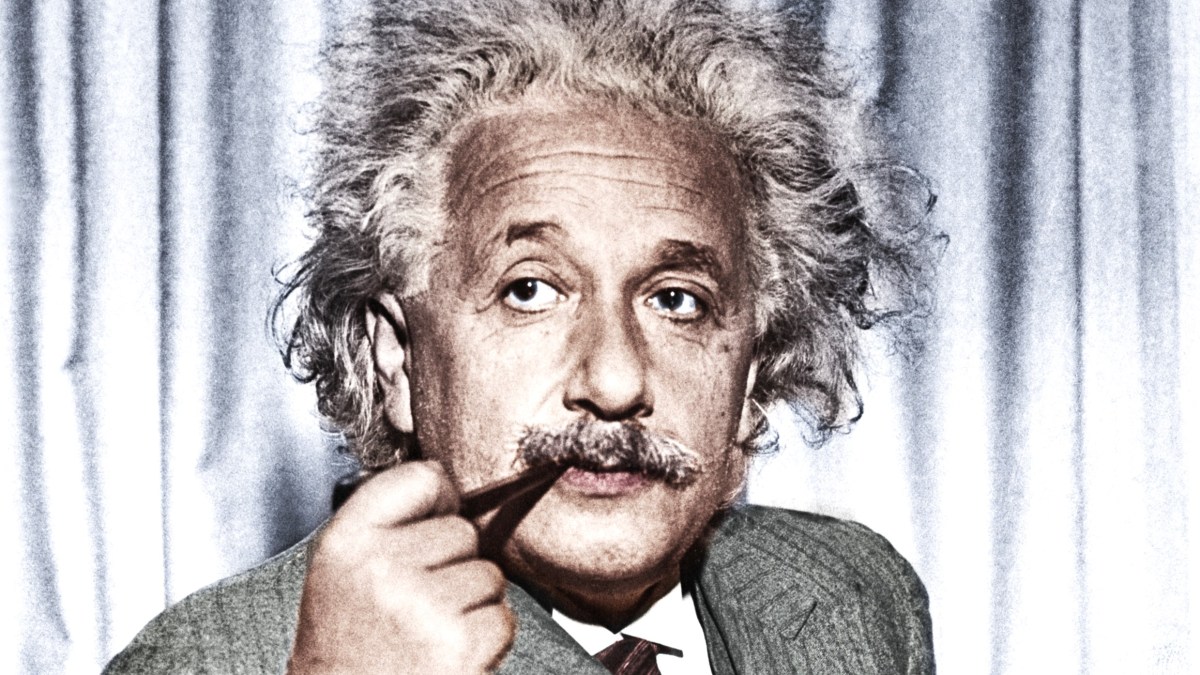

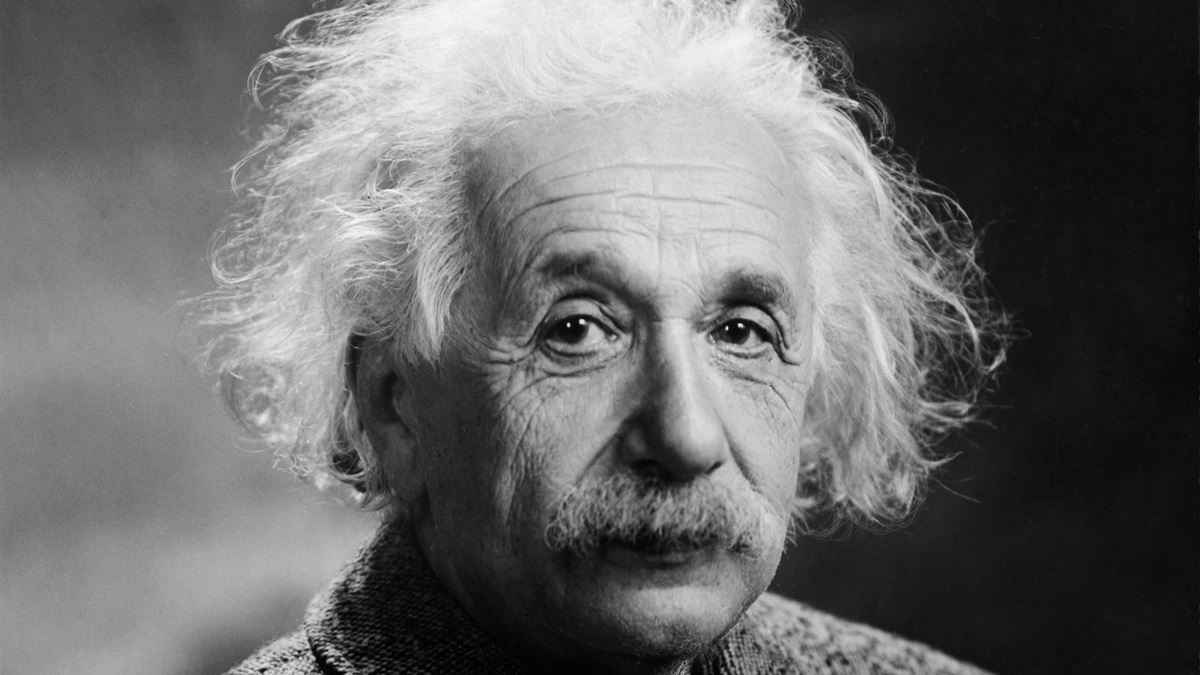

Albert Einstein, one of the greatest scientists of all time, was a German-born physicist known for developing the theory of relativity with the mathematical formula E=mc2. He was also awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921 for his contributions to theoretical physics.

In the last half of Einstein’s life, he suffered from several medical issues including digestive system problems, gall bladder inflammation, stomach ulcers, liver cirrhosis, and intestinal pain. He underwent surgery to remove cysts in 1948 when he was 69 years old, and it was during the procedure that it was discovered he had an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA).

An aortic aneurysm often develops in the lower abdomen, which can cause constant pain in the area as the aorta balloons. The method to fix the medical issue back then isn’t as advanced as it is today. Einstein’s doctor reinforced the blood vessel wall with cellophane, which was the best solution at that time. However, there was still the risk of the aorta rupturing.

In 1955, Einstein was working on a speech in his office when he experienced chest and abdominal pain. He was brought to Princeton Hospital where doctors said that he needed to undergo surgery to repair a ruptured blood vessel in his aorta. However, Einstein refused, saying, “I want to go when I want to go. It is tasteless to prolong life artificially. I have done my share; it is time to go.” He died on April 18, 1955, at 76 years old, just a day after going to the hospital. Before his death, he left specific instructions for his body to be cremated and the ashes scattered at an undisclosed location, as he didn’t want people from “worshipping” his dead body.

Albert Einstein’s last wishes

Einstein’s body was cremated on April 20 in a strictly private ceremony. Just a day later, Einstein’s son, Hans Albert, was shocked and incensed to read an article in The New York Times, saying his father’s brain had been removed during the autopsy.

Hours after Einstein’s death, Dr. Thomas Harvey conducted an autopsy, and it was then that he retrieved the scientist’s brain. Furthermore, he removed the eyeballs and gave them to Dr. Henry Abrams, Einstein’s optometrist. Einstein’s family didn’t give the pathologist permission to do so, nor did they know this had been done before the article was published.

Einstein’s family was deeply unhappy and they demanded that Dr. Harvey return the brain. However, Dr. Harvey convinced Hans Thomas that studying his father’s brain would benefit the scientific community, and he promised that the findings would be published in reputable scientific journals.

The public was interested in whether Einstein’s brain had certain structural differences from other people’s brains that made him a genius. Despite being outraged at what Dr. Harvey did, Hans Thomas eventually agreed to what the pathologist wanted to do on the condition that the brain would only be used for scientific studies.

What did Dr. Harvey do to Einstein’s brain?

Shortly after acquiring Einstein’s brain, Princeton Hospital let go of Dr. Harvey for his controversial and unauthorized actions during the autopsy. He then headed to the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia where he cut Einstein’s brain into hundreds of pieces and preserved most of the pieces in celloidin, a compound used for embedding specimens for microscopy. Other pieces were placed in two jars that he kept in his basement.

Unfortunately, Dr. Harvey didn’t have the expertise to study Einstein’s brain. As a pathologist, he was adept at performing postmortem examinations, but he wasn’t a brain doctor. He sent some samples to some neuropathologists to study, but he made his own observations as well. Since the public had knowledge that Dr. Harvey had the famous scientist’s brain, the media often hounded him for information or updates about what was happening with the studies, but he was evasive and said that the results would be published “soon.” The first study published was in 1985, 30 years after Einstein’s death.

Meanwhile, Dr. Harvey’s life went into shambles. His marriage fell apart and he moved to Wichita, Kansas, and then later to Weston, Missouri. He kept the jars with pieces of Einstein’s brain with him, concealed in a box with a beer cooler on top. In 1988, Dr. Harvey lost his medical license after failing a competency test. Afterward, Dr. Harvey moved from location to location, still keeping the jars with him. By the end of his life, it’s reported that he lived in a small apartment where he kept the jars in a closet. He eventually gave the jars to a pathologist at the University Medical Center of Princeton in 1998. Harvey died in 2007.

Where are the pieces of Einstein’s brain today?

Pieces of Einstein’s brain are in different parts of the United States. Harvey sent slides to doctors and scientists who may have kept the specimens for themselves. It’s also known that the jars Harvey kept for himself are now in Princeton. The National Museum of Health and Medicine in Maryland also has 350 slides in possession, which they bring out for exhibits from time to time. However, there is one place where Einstein’s brain is permanently displayed — the Mütter Museum. As for Einstein’s eyeballs, they are believed to be stored in a safety deposit box in New York City, though no one knows for sure.

The Mütter Museum, located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, is a medical history museum with thousands of artifacts, including specimens, medical instruments, and models. It was only in 2011 that the museum was given Einstein’s brain slides. When Harvey had the slides made after he left Princeton, he went to the University of Pennsylvania to a lab technician, Marta Keller, who was renowned for making slides of specimens. Some of the slides were given to William Ehrich, a well-known neuropathologist in the state who worked at Philadelphia General Hospital.

Ehrich stored the slides until he died in 1967. Ehrich’s wife then passed the slides to another pathologist at Philadelphia General Hospital, Allen Steinberg, who gave them to Ehrich’s former student, neuropathologist Lucy Rorke-Adams. For years, she had the box of slides on her work desk but in 2011, she decided that it was best if they were donated to the Mütter Museum. “I think the time has come to turn them over to the College and the Mütter Museum as they are a part of medical history,” Rorke-Adams said.

Today, visitors at the museum can view 46 slides of Einstein’s brain and even see one slide under a magnifying lens. Each slide has a sliver of the brain that measures about 20 to 50 microns (0.02 mm to 0.05 mm) thick. The specimens of Einstein’s brain are one of the highlights of the museum, but, as he explicitly didn’t want his body to be worshipped after his death, we suspect Einstein’s ghost is very, very cross.