The signing of the Declaration of Independence is a pivotal moment in American history, marking the birth of a new nation.

The movement toward independence began years before the actual signing, as tensions between the British crown and the American colonies escalated. In June 1776, with conflicts already underway and following a year of open warfare, the Continental Congress convened to discuss the colonies’ next steps. On June 7, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia presented a resolution urging Congress to declare independence from Britain.

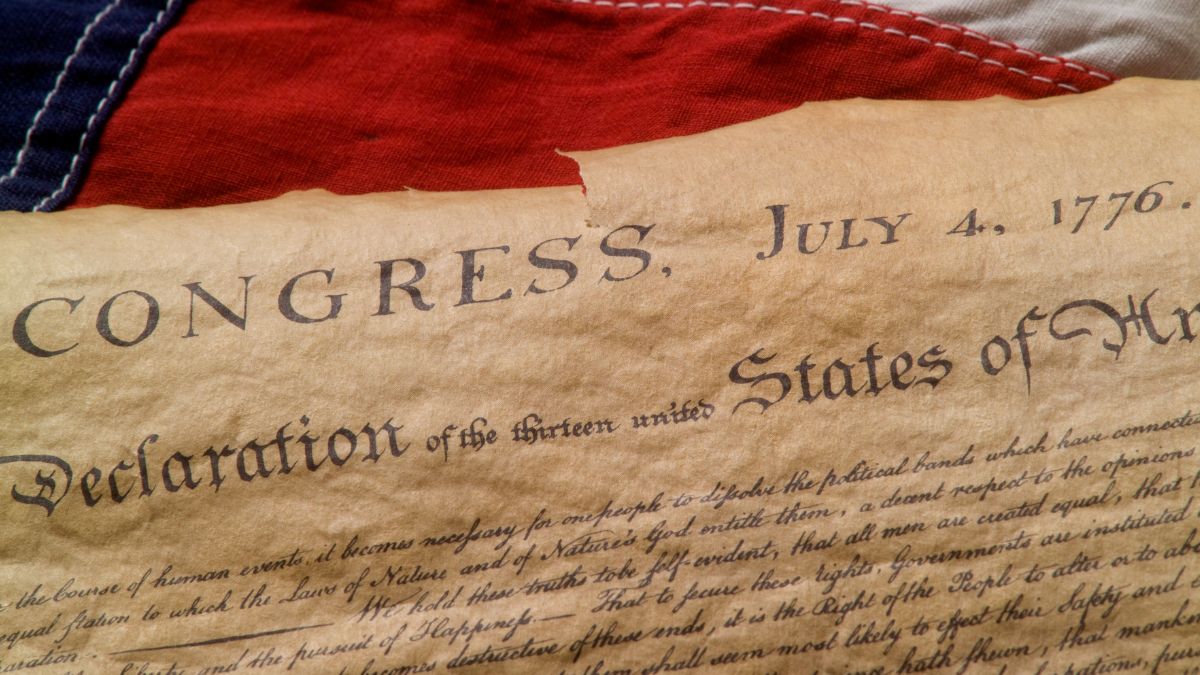

On July 2, 1776, Congress officially passed Lee’s resolution for independence. This date was later described by John Adams in letters to his wife as the day that would be celebrated by succeeding generations as the anniversary festival of American independence. Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence itself on July 4, 1776, after further debate and revision. It was then that the famous line “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…” was officially agreed upon and the document was approved.

However, the popular image of all the 56 signatories lining up and signing the Declaration on July 4th, 1776, is, unfortunately, more a product of collective imagination and patriotic fervor than of factual accuracy. In reality, the Continental Congress officially adopted the Declaration on the 4th of July, but the signing itself wasn’t such a synchronized affair.

After its adoption, the Declaration was sent to a printer named John Dunlap to make copies, known as the Dunlap Broadsides, which were distributed to the colonies. The actual signing of the Declaration began on August 2, 1776, when the engrossed copy was ready. Not all members of Congress were present, and some signed later. Some of the notable figures who signed the Declaration include John Hancock, President of the Congress, whose bold signature is the most recognizable. Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, and John Adams, members of the drafting committee, also signed, along with other prominent leaders such as Samuel Adams, Benjamin Rush, and Charles Carroll of Carrollton, one of the wealthiest men in America and the only Catholic signer.

The last signer, Thomas McKean of Delaware, did not sign until 1781, by which point the ink on the other signatures was probably dry. But better late than never, right? Interestingly, two signers of the Declaration, John Dickinson and Robert R. Livingston, were not present on August 2 and never signed the parchment copy. Instead, Dickinson’s name was included on the printed copies, while Livingston’s name was omitted altogether.

In conclusion, while the exact hour of the Declaration isn’t officially recorded, perhaps it’s for the better. It keeps our focus on the broader narrative—the unfolding drama of courage, conviction, and, yes, a bit of procrastination, which is so inherently human.