We’ve all been there. You’re the leader of a revolutionary communist party with ambitions to make your underdeveloped country an industrialized powerhouse. You might even dub this a “leap” into the future. But how do you drag a nation of illiterate farmers along with you?

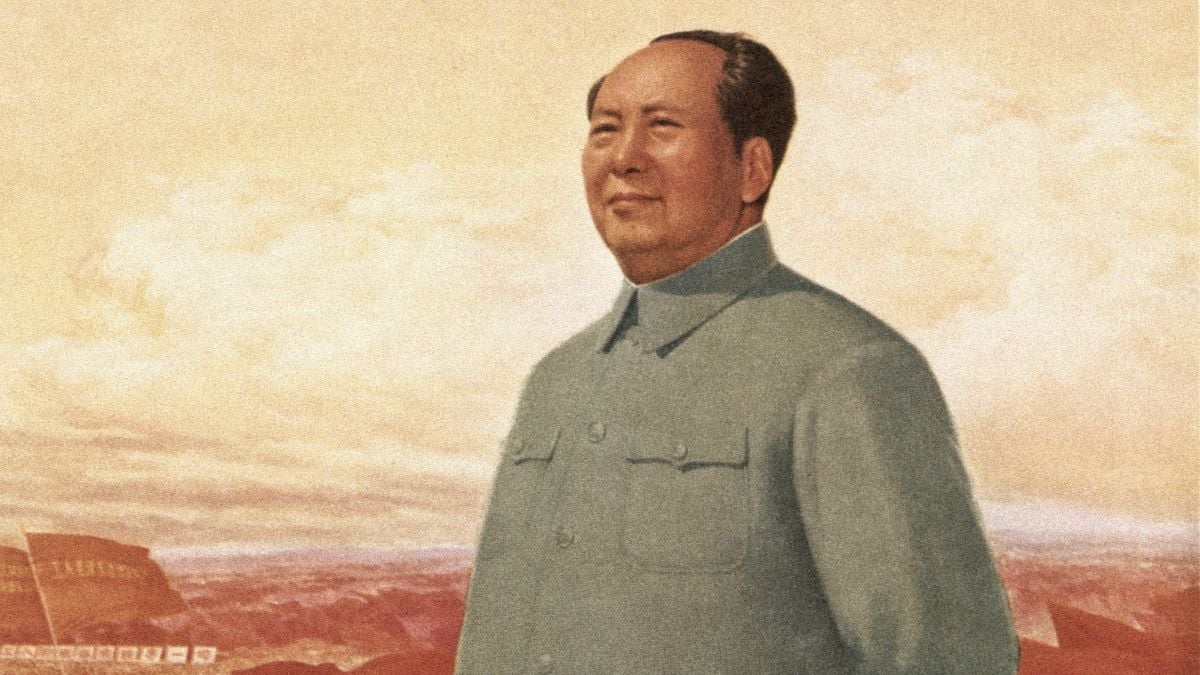

This question was troubling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Mao Zedong in the mid-1950s. China, a country rich in natural resources and labor, wasn’t pulling its economic weight, particularly in comparison to superpowers like the United States and the Soviet Union.

It was time for a plan. It was time for a Great Leap Forward.

One of the poorest countries in the world

In 1949 China was among the poorest countries in the world. The Pacific conflict had seen China become a major battleground, with Imperial Japan attempting to take over the country. Now that this problem is solved it’s time for change.

Fueled by the fervor of Marxism, Chairman Mao aimed to show that communism could transform the country for the better, declaring at a 1955 CCP conference that China would soon: “catch up with and surpass the most powerful capitalist countries.”

It’s an ambitious goal. Perhaps too ambitious…

The leap begins

The overall philosophy behind the Great Leap Forward (and pretty much the core tenet of communism) is that the desires of an individual are overruled by the needs of society. In theory, if everyone works toward a common goal then the material standards of living will increase and everyone’s life improves. Sure, you might have to get rid of a few dissidents along the way, but you can’t make a delicious communist omelette without breaking a few counter-revolutionary eggs.

As such, the Chinese people became part of a vast collectivist experiment, in which every individual was encouraged to pull together for the benefit of the country. In practise this translated to mandatory communal farming programs, in which people would be made to farm crops (i.e. grain). Most of this would be given to the state, with what’s left used to feed the farmers.

In addition, peasants were encouraged to support the growth of China’s steel industry by constructing backyard furnaces in which to smelt steel from scrap iron. People were also conscripted into massive irrigation works to further improve agriculture, along with various other work programs to drag China into the modern age.

The results

Things did not go as planned. And that’s putting it lightly.

The exciting new grain planting techniques were based on Lysenkoism, a discredited pseudoscience. Rather than increase production, its recommendations had the opposite effect. Admitting that the science was incorrect would have political implications for their relationship with the Soviet Union, so they (literally) ploughed ahead towards disaster.

Each collective farm and region was given wildly ambitious crop quotas, with severe punishments for officials who failed to meet them. This meant that the crops that were supposed to be earmarked to feed the farmers went towards the quota, and people starved.

As you might expect, the backyard furnaces proved incapable of producing high-quality steel, and most of the peasant’s iron items (cooking equipment, tools etc) were fed into the furnace to create useless “pig iron”. To fuel these furnaces forests were cut down for fuel, causing environmental destruction and raising the risk of flooding. And, as you might expect from illiterate peasants being told to make steel, there were constant fires and injuries.

And, at the higher levels, the power of senior communist officials was so great that their subordinates would not report bad news to them. After all, these programs were founded on the core tenets of Marxism. Arguing they weren’t working would be arguing that communism wasn’t working, and that’s not going to go well for any CCP bureaucrat.

This (and many other bad decisions) created a perfect storm of misery, and resulted in what’s now known as the Great Chinese Famine. Death estimates range from 15-55 million people, potentially making this the most deadly famine in human history.

Lessons learned

Mao would never admit that he’d personally ushered in such a disaster. Still, even he later said his government had “extended the infrastructure battlefront too long” and that he’d learned a valuable lesson: it’s “best to do less and well”.

A fine moral, it’s just a shame tens of millions of peasants had to die to get there.