Tensions in the U.S. Senate escalated during the 19th century as groups pro and against slavery jockeyed for power. Faced with deep divisions, politicians needed something to keep the peace and the Missouri Compromise did that. For a few decades, anyway.

In the early 19th century, the United States was much smaller than today. Part of what’s now the national territory belonged to European countries such as France, Spain, and England. France, in particular, held a vast area of land in the middle of the country, around states such as Louisiana and Missouri. In 1803, the U.S. bought the lands from France, almost doubling the country’s territory.

On the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, France struggled to find enough money to fight Napoleon Bonaparte’s European wars. Since the European superpower was also dealing with a rebellion in the Haiti colonies, which would result in their independence in 1804, Bonaparte saw no reason to hold American lands. So, through the Louisiana Purchase deal, the French emperor sold his lands, helping the U.S. to expand further towards the West.

The lands acquired in the Louisiana Purchase offered vast fertile territories and a valuable transportation route along the Mississippi River. Nevertheless, the deal also created geopolitical issues, as the Senate was forced to decide how the lands would be split and whether slavery would be permitted in the new states formed after the deal.

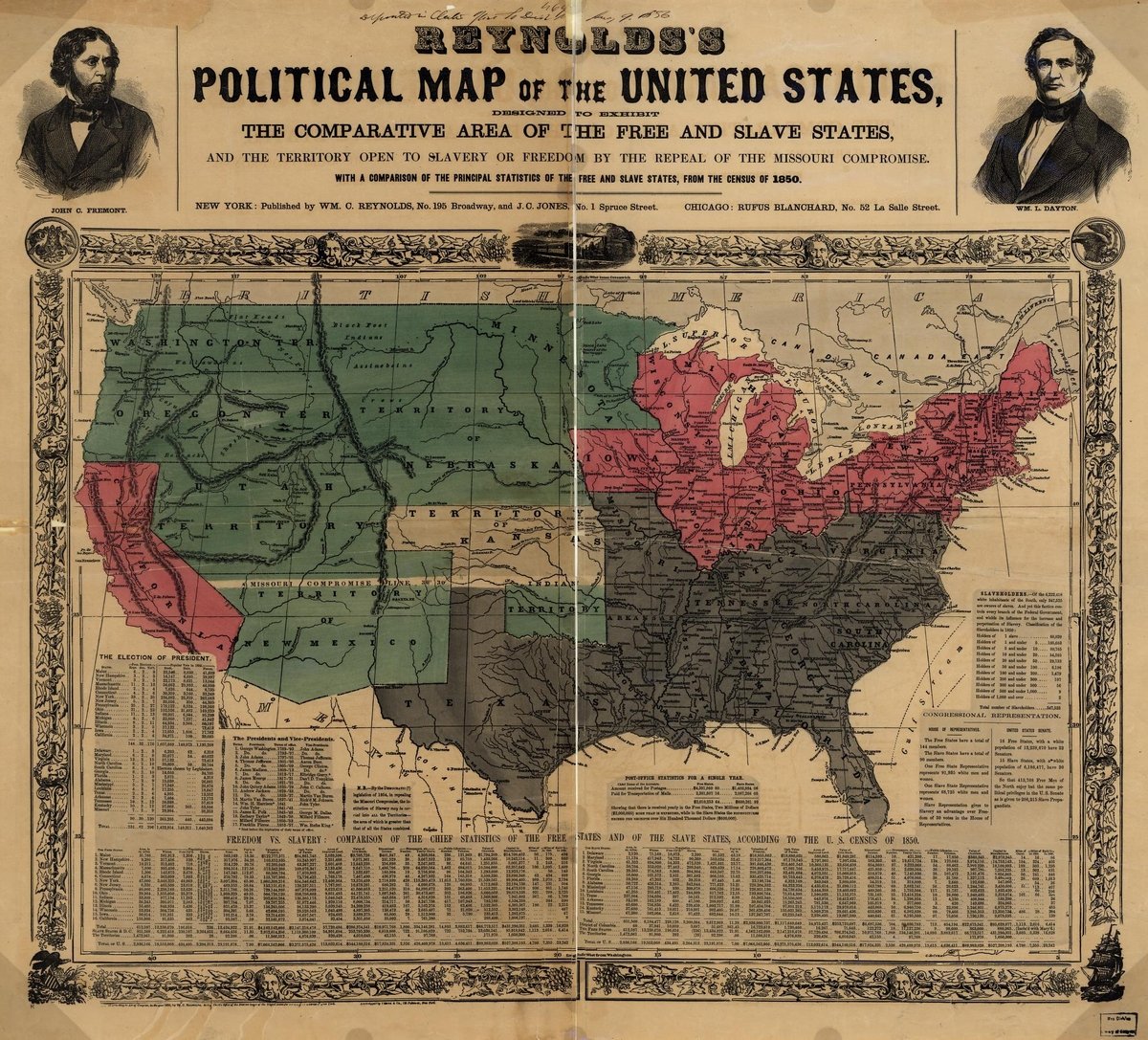

In the early 19th century, the Senate recognized 22 states, equally divided between free and slave states. This equanimous division helped to keep politicians in check, as each side of the conflict held the same amount of power. However, when the Missouri region asked to be recognized as a state in 1819, adding a new slave state threatened the delicate balance of the U.S. Senate, an issue that the Missouri Compromise temporarily solved.

What did the Missouri Compromise define?

Signed in 1820, the Missouri Compromise reorganized the political territory of the U.S. to appease both free and slave states. The legislation allowed Missouri to become a new slave state with representatives in the Senate. At the same time, the region of Maine, previously belonging to Massachusetts, became a free state. That meant the Northern and Southern factions of the Senate remained with the same number of representatives, delaying the Civil War by a few decades.

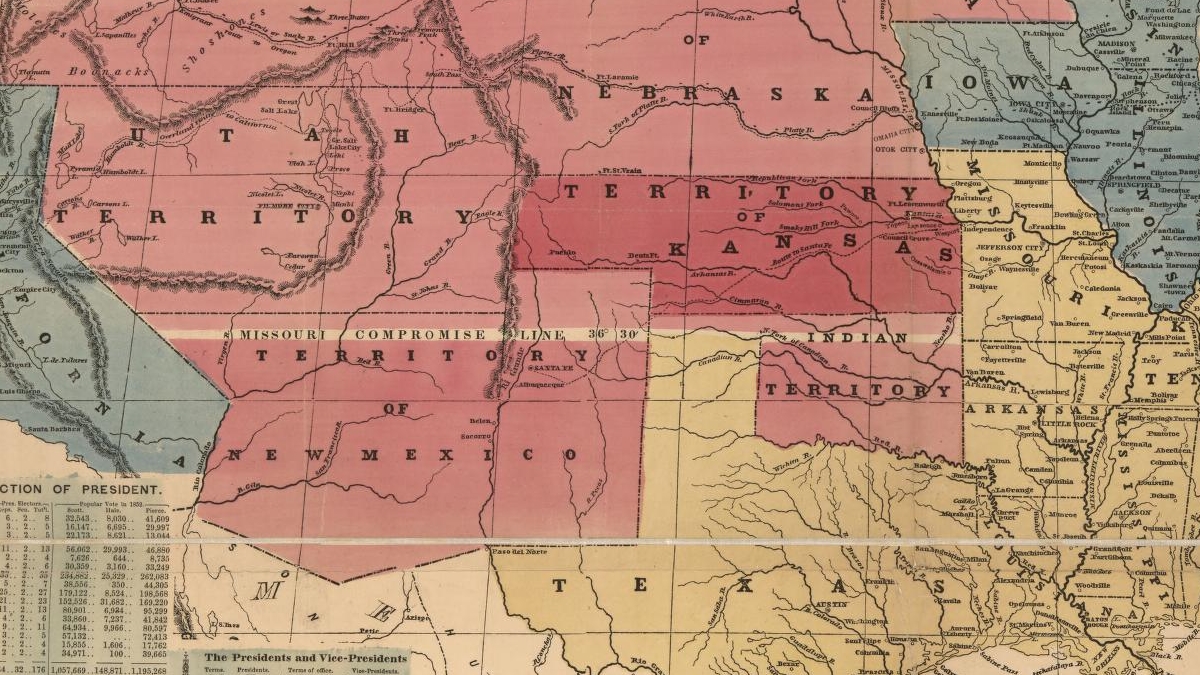

The Missouri Compromise also established the 36°30′ north latitude line as the limit for slavery in the remaining unorganized Louisiana Purchase territory. Lands above these imaginary lines would be considered free territories, while the grim business of slavery kept booming south of the line. In short, the Missouri Compromise also defined the rules for any new state created from the Louisiana Purchase lands, avoiding further conflict regarding adding representatives to the Senate.

While the Missouri Compromise helped to keep the peace for 30 years, the legislation also revealed the depths of the schism between the North and the South. Both factions had irreconcilable worldviews, which the law made all the more perceptible. So, while the legislation forged in 1820 prevented a war from happening at the time, it also made it clear that there would be no way to stop people from raising arms if slavery wasn’t abolished in the entire country. Unfortunately, the war eventually came in 1861’s Civil War, one of the bloodiest chapters in U.S. history.