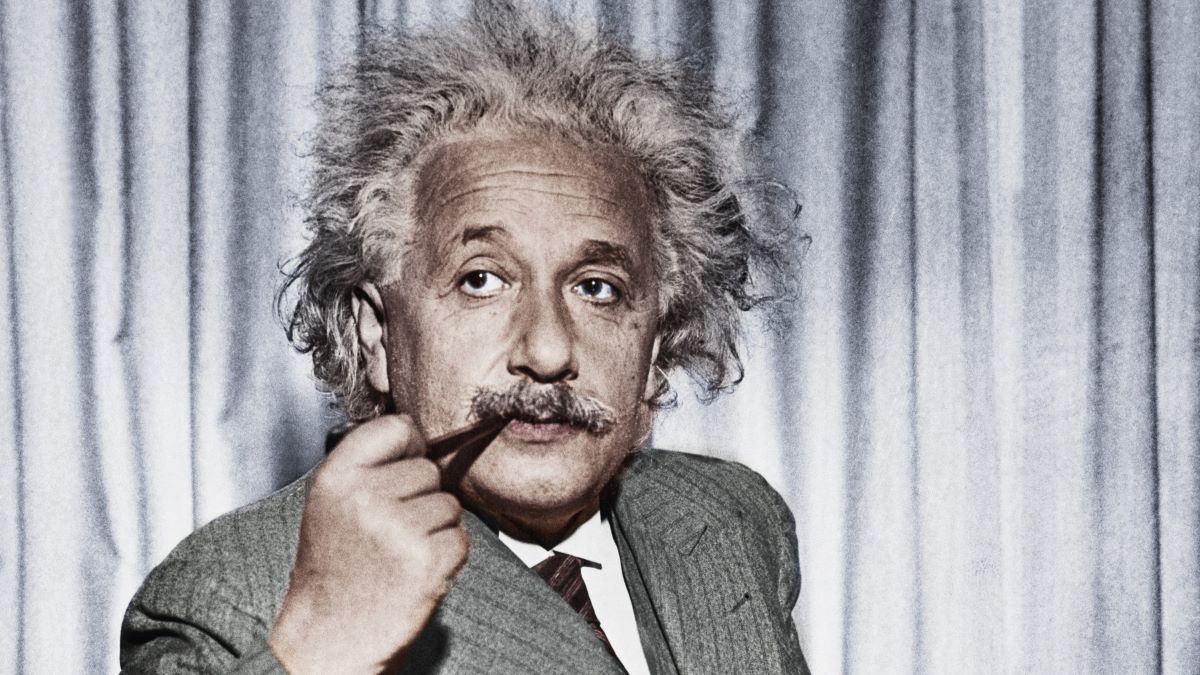

When most folks think of Albert Einstein, they picture him with that wild shock of white hair, twinkling eyes, and maybe that famous tongue-out photo that makes him look more like a playful uncle than the architect behind the theory of relativity.

However, what often gets overlooked are the stories of Einstein’s two sons, Hans and Eduard, who grew up in the shadow of their famous father. Einstein and his first wife, Mileva Marić, didn’t have the smoothest marriage, and it wasn’t the best environment for kids to grow up in. They were always arguing and had a lot of tensions, partly because they were both strong-minded and had different expectations from life. Albert was chasing the universe, while Mileva, also a physicist, struggled to find her own space in the scientific world, which at the time was not very welcoming to women.

When Einstein and Mileva finally divorced in 1919, it impacted heavily on the children. Eduard, the younger son, was particularly sensitive. He was a smart kid, interested in poetry, and had ambitions to be a psychiatrist.

The first hints of trouble began in Eduard’s late teens. He started to show signs of severe mental distress, which eventually led to a diagnosis of schizophrenia in his early twenties. Schizophrenia is often accompanied by hallucinations, delusions, and a profound disruption in cognitive functions, all of which Eduard experienced. The condition ravaged his aspirations and gradually decimated his ability to function independently.

Albert Einstein’s reaction to his son’s illness was, well, complicated—and not exactly Father of the Year material. He struggled to understand and accept his son’s illness. In a 1917 letter to a colleague, he wrote:

My little boy’s condition depresses me greatly. It is impossible that he would become a fully developed person.

While Einstein supported Eduard financially, he was often distant, consumed by his work and his own sprawling set of personal issues, including a new marriage with his cousin (yikes!).

In 1932, as Hitler rose to power and the situation in Berlin became increasingly dangerous for Jews, Einstein took a position at Princeton University and left Europe. Eduard, however, remained in Switzerland with his mother. Eventually, in 1933, he was admitted to the University of Zurich’s psychiatric clinic, Burghölzli.

Except for a brief stint where he lived outside the clinic, Eduard spent the rest of his life in psychiatric institutions. He underwent various treatments, including insulin shock therapy, which was a common but controversial practice at the time. None of these interventions proved effective, and Eduard’s condition only worsened. Ultimately, Eduard passed away in 1965, at the age of 55, having never fully recovered from his illness. Albert Einstein, who had passed away a decade earlier, never saw his son again after leaving Europe.

Hans Albert, on the other hand, managed to carve out a more stable path for himself as an engineer and a teacher. But even he couldn’t completely escape the shadow of his father’s fame or the effects of the family’s strained dynamics.