The atomic bomb is almost synonymous with Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Despite their intrinsically linked nature, the city wasn’t the only site labeled by the U.S. military as a valuable Japanese targets at the end of World War II. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were just two potentials in a long list of possible objectives.

There is ongoing debate over the ethics of dropping the biggest bomb implemented during conflict in human history, but one thing is certain. The destruction of these two cities serves as a stark reminder of the human cost of war.

Why did the U.S. bomb Hiroshima?

There were months of work behind the decision to bomb Hiroshima. It wasn’t as if the city was the only option. A panel of military officers and scientists debated which target to hit, seesawing between Japanese military installations and cities. Historian Alex Wellerstein told NPR that there were even plans to simply display the bomb, without demonstrating its awesome power.

An attempt to showcase the new weapon without first proving its lethality was deemed useless. A key component of the use of the bombs was the psychological effect its destructive force would have on the Japanese. The excessive force, the U.S. hoped, would lead to an unconditional surrender.

A “visual bombing” was necessary not just to prove how determined the U.S. was to end the war, but also for them to understand the full breadth of the “gadget” they were dropping. The bombs were a relative unknown. Those in charge of the Manhattan Project had minimal chance to test the “gadget.” Minimal testing had been performed outside of Los Alamos, New Mexico during the Trinity Nuclear Test, but it had never been observed in action.

Dr. Dennison, who was tasked with gathering weather data noted that there were likely only 6 viable days for a visual bombing run in August and that the team would only know potential viability within 48 hours of a proposed run. The weather during the summer months in Japan was rainy, hot, and unpredictable. With so many unknown variables, the visual bombing mission had several backup options in addition to the primary target.

“When the mission does take place there should be a spotter aircraft over each of three alternative targets in order that an alternative target may be selected in the last hour of flight if the weather is unpromising over the highest priority target,” Dr Dennison’s memo notes.

Declassified military documents show a range of targets, but the 20th Air Force had been “bombing the hell” out of Tokyo, Yokohama, Osaka, Kyoto, Kobe, Yawata, and Nagasaki for months. The cities were key positions for the Japanese – they housed airplane and weapons manufacturing plants, military bases, and military depots, and most importantly, they had large populations. They also prioritized “large urban areas of not less than 3 miles in diameter existing in the larger populated areas,” and targets near Tokyo.

Culturally significant cities like Kyoto were high on the list, “from the psychological point of view, there is the advantage that Kyoto is an intellectual center for Japan and the people there are more apt to appreciate the significance of such a weapon,” Dr. Stearns, who was tasked with finding the perfect target, postulated in a 1945 memo to General Grove.

The Air Force planned to drop “100,000 tons of bombs on Japan per month by the end of 1945,” leaving many tactically significant cities partially demolished, and civilians dead by the thousand. The preexisting damage wasn’t ideal. The U.S. wanted to make sure the power of the weapon could not be misunderstood.

By attacking partially destroyed cities, the damage could be seen as cumulative, the death counts misconstrued, and the psychological toll of the bomb greatly reduced.

Hiroshima was the largest untouched target with a population of 255,000 people. Its urban development was also fairly contained, unlike Tokyo which sprawled far beyond Little Boy’s damage radius of 1.3 kilometers (just under 1 mile). Dr. Stearns wrote of the city,

“This is an important army depot and port of embarkation in the middle of an urban industrial area. It is a good radar target and it is such a size that the large part of the city could be extensively damaged. There are adjacent hills which are likely to produce a focusing effect which would considerably increase the blast damage. Due to rivers, it is not a good incendiary target.”

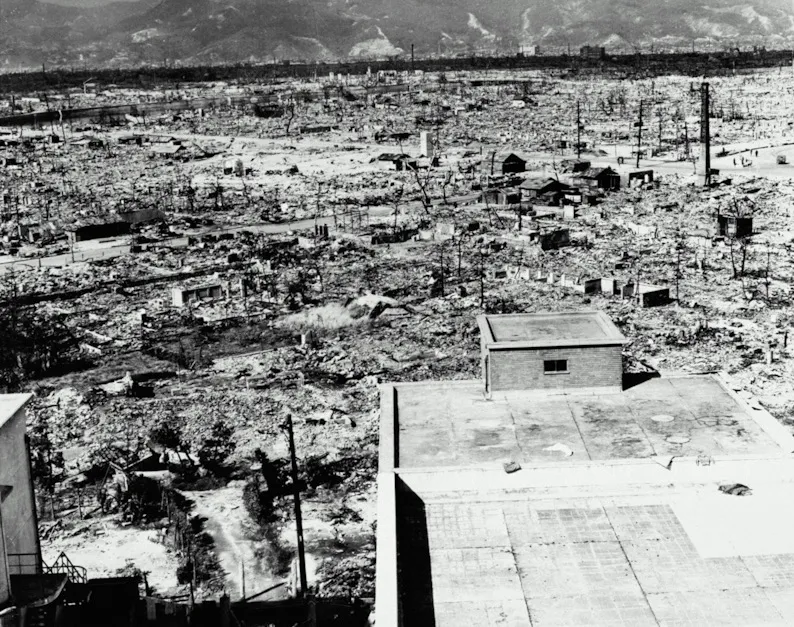

The Enola Gay a B-29 bomber dropped Little Boy on Hiroshima at 8:15 am on August 6. It exploded 2,000 feet above the city destroying 5 square miles in the city with a blast equal to 12-15 tons of TNT. Approximately 66,000 people died and another 69,000 were injured.

The blast didn’t have the immediate effect the U.S. had intended, however, and 3 days later they dropped a second bomb on Nagasaki.

Japan surrendered nearly a month later on September 2, 1945, ending World War II.