Warning: this article contains spoilers for both Barbie and Oppenheimer.

The Barbenheimer hype has been very real, and after months of anticipation, it appears that both films are exceeding their projected box office projections and then some. While the movies have been the subject of controversy thanks to their themes and subject matters, on the face of it, they appear to be very different viewing experiences. After all, one is about a plastic doll who brought about a revolution in how young girls played, while the other is about a nuclear physicist and genius who was driven by a fear of Nazism and a sense of duty to help create the worst weapon humanity has ever produced.

However, upon closer inspection, it seems that Barbie and Oppenheimer might have a little more in common than a release date. If you watched the two films as a double feature over the weekend, or just want to know how two diametrically opposing seeming films could be seen as linked, then read ahead to find out all the ways Barbie and Oppenheimer are actually similar.

An outstanding ensemble cast, led by a brilliant star

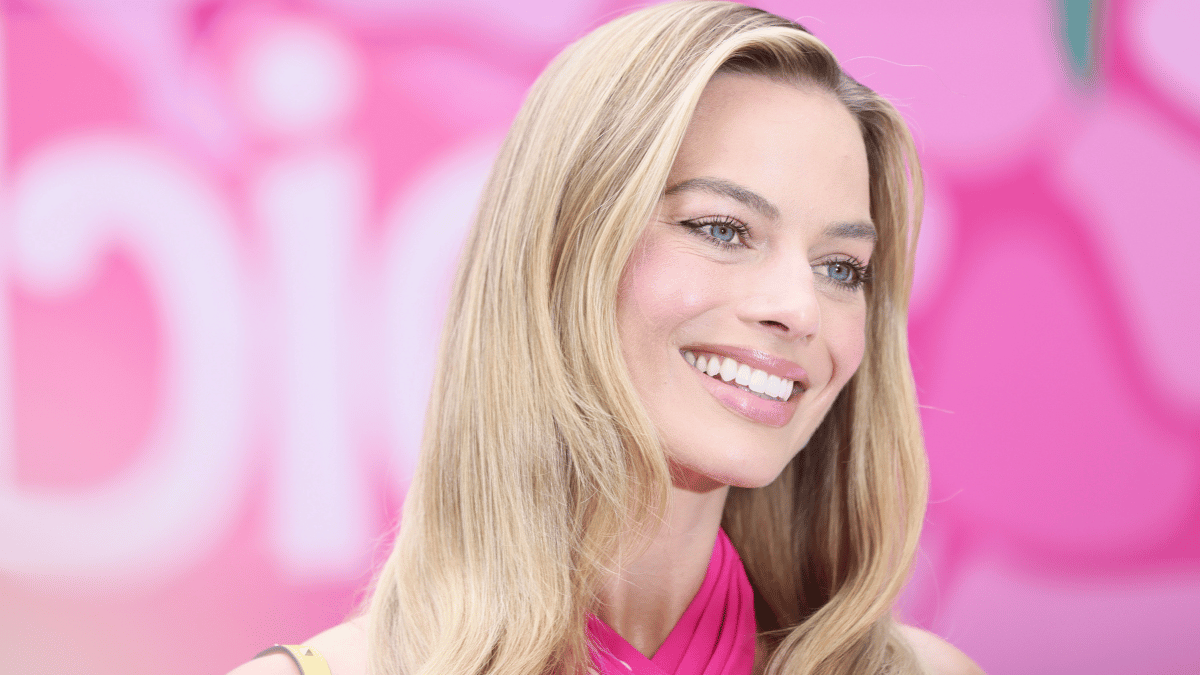

While both films are mostly focused on their titular characters, Barbie and Oppenheimer are also lucky enough to have some of the biggest names in Hollywood supporting their two stars. Margot Robbie is backed by Ryan Gosling, Kate McKinnon, Issa Rae, Michael Cera, America Ferrera, Will Ferrell, and even pop star Dua Lipa in her feature film debut. Yet, Oppenheimer boasts just as star-studded a call sheet, with star Cillian Murphy acting alongside the wonderful Florence Pugh, Emily Blung, Robert Downey Jr., Rami Malik, and Matt Damon.

Proust and his madeline

J. Robert Oppenheimer was a famously philosophical and well-read man who knew multiple languages and could often be found pouring over both ancient and modern texts that didn’t directly relate to physics. So, it makes sense that he was a huge fan of the influential French novelist Marcel Proust, who is most known for his epic tale In Search of Lost Time (À la recherche du temps perdu) While the majority of Barbie cultural references are based on film (including the wonderful opening homage to 2001: A Space Odyssey), at one point Robbie’s Barbie is placed into an old box, where she makes a reference to the famous French author, which is followed by a joke by Ferrell’s character about how the Proust Barbie was a commercial failure (this is also the only Barbie that’s mentioned in the film that doesn’t have a real life counterpart).

As those versed in literary history will know, one of the most important techniques Proust made popular was his use of involuntary memory, which stems from a famous passage near the beginning of In Search of Lost Time, in which the narrator eats a madeline biscuit and is transported back to their childhood, much like Barbie is transported back to her memory of being boxed when she smells the box she’s in.

Existentialism

Although it might superficially seem like a light-hearted comedy, Greta Gerwig’s Barbie is really all about the doll finding meaning in her existence, especially in a strange, absurd, and often nonsensical world. After all, the film ends with Barbie becoming human, and coming to terms with the fact that real life is messy and full of ups and downs. The links between Oppenheimer and that sort of thinking are also quite clear, with the physicist often seen fretting over what his work will do to humanity, and the very nature of the physics he studies being concerned with what life is, and if it means anything.

This is all linked to the philosophy of existentialism, which means another French connection between the two films, as the word was coined by the French philosopher Gabriel Marcel and is most famously applied to Jean-Paul Sartre. Other famous proponents of the school of thought are Heidegger, Kierkegaard, and even the novelist Dostoyevsky.

The contemplation of mortality

One of the biggest clues audiences got about the much-hushed plot for Barbie before its release came from the trailer, where in the middle of a fun dance routine, Robbie’s Barbie asks the others if they’ve ever thought “about dying.” This is eventually revealed to be because America Ferrera‘s character, who has a cross-world connection with Barbie, is in the middle of a somewhat depressive episode, dealing with existential dread (there’s that word again). Of course, in Barbie Land, everything is supposed to be perfect, which means no death. Yet, Stereotypical Barbie has thoughts of the beyond, which ties into the bigger themes of the film about self-actualization, the meaning of being human, and what mortality means to a being that hasn’t considered it before.

The notion of death and mortality isn’t so much hanging over Oppenheimer but practically drowning the narrative. Not to be too blunt about it, but this is a movie about a weapon of mass destruction that could have ignited the entire atmosphere, so it would be harder for questions of mortality to not be touched upon by Nolan and his crew.

They’re both made by auteur directors who’ve been given massive budgets

Prior to Barbie, Greta Gerwig had directed the indie sleeper hit Lady Bird, and a wonderful adaptation of Little Women, so this was her first major studio flick — and as th

e all-encompassing marketing campaign attests to, the money was very much there for her to do what she wanted. Both her previous films were very much character-driven, delivering nuanced portraits of women on the edge of adulthood, so it’s fair to say that she’s proven herself at being an adept filmmaker.

Nolan is also known for his complex storytelling and use of experimental ideas to tell a story. However, he’s been blessed with multiple big budgets in the past (Interstellar, The Dark Knight), so the huge pool of money available to him for Oppenheimer wasn’t as much of a surprise as the endless cash Gerwig received.

A dislike of CGI for vital scenes

Nolan has famously said that he didn’t use CGI when filming the A-bomb scene in Oppenheimer, and has spoken before about his general dislike of the overreliance on computers when it comes to action scenes. However, what’s less known is that Robbie’s famous arched feet scene in Barbie was done with the A-lister hanging on to a bar, instead of using computers. A little less impressive than a nuclear explosion, but still cool nonetheless.

Famous figures with complicated and controversial legacies

You could write countless essays on the cultural impact of Barbie (and plenty of people have). The doll has been seen as a feminist icon, a symbol of patriarchal subjugation, a tool for racism, a mascot for a capitalist hellscape, and so on and so forth. While Gerwig’s film tries to address many of these ideas, there’s just too much baggage for even the talented director to fully encompass everything that Barbie means to everyone.

Oppenheimer was also a highly controversial figure, and not just because of his role in ushering in the age of nuclear weapons. He was famously involved in many left-wing causes, was a Jewish American who was sympathetic to some minorities while also ignoring the plights of others (especially Hispanic and Native folks who were residing in New Mexico while the Manhattan Project was going on), cheated on his partners several times, and utilized his political standing to try and shape nuclear policy. Even with its three-hour runtime, Nolan can’t fit all that in, but he does a good job of trying.

Horses, horses everywhere

The horse has long been a symbol of a drive to explore and dominate, an idea hastened by romanticized notions of explorers riding on horseback into parts unknown. In Oppenheimer, the titular character is often seen riding on his horse with his wife (played by Emily Blunt), and horseriding is used as a metaphor for their relationship. In Barbie, Ken’s lessons in patriarchy lead him to believe that the horse is an intrinsic part of a world with men at the forefront, which, frankly, isn’t a completely incorrect analysis of the animal’s place in our culture.

Birthing countless silly hot takes from “I am very smart” types

One of the worst things about social media is some people’s insistence that every post or comment needs to be full of context that reflects their life and opinions, with many genuinely believing it’s a form of violence or oppression when a viewpoint isn’t mentioned. Naturally, these two popular films have been subject to silly hot takes from the most embarrassing type of terminally-online people, most of which are the result of pre-conceived opinions that the watchers had before seeing the film (and, in many cases, they admit to not even having watched whatever movie they’re criticizing yet).

Barbie is a film made by a woman, about a product that was mostly used by women. Yet, so many angry keyboard warriors and creepy little men are incensed at the fact it portrays things from what most would consider a feminine standpoint. There are those complaining that Barbie Land is misandrist, which means they missed the entire point of the film, which is simply a reflection of our own society. For example, at the end, Ken asks for more representation and is told it will come slowly. Barbie Land is, in many ways, a reversed version of ’60s America, and after the Civil Rights movement women and people of color were effectively told they were equal, but not allowed to really be in positions of power yet. Sound familiar? Then there’s the outrage at America Ferrera’s rant about how hard it is to be a woman sometimes, which some people seem to think should have been followed by a ten-minute presentation on the ways in which men are subjugated by society. While this was inevitable, it is funny to see just how predictable the complaints were.

Oppenheimer has also been subject to similarly uneducated takes on its issues, most of which seem to stem from confusion about the purpose of a biopic. A biopic isn’t a documentary, so the fact Oppenheimer doesn’t focus on the impact of the bombs in Japan is not a particularly relevant criticism (also, perhaps the best way to learn about the impacts of the bomb would be checking out Japan’s take, seeing as they have a pretty expansive film industry. Or you could just remember Godzilla exists).

A number of folks have also been complaining that the film erases the stories of the Hispanic and indigenous people living in the area the Trinity test took place in. However, the film is from the physicist’s perspective, and Nolan does in fact make a very relevant comment about how ignored these people were by only having Oppenheimer mention “the Indians” once the test bomb was dropped on Los Alamos, when he suggests giving the irradiated land back to them. And then there’s the dull, pop-feminist take being bandied around by mostly wealthy white women that a film from the perspective of a man who was dismissive of the women in his personal life doesn’t focus enough on them.

Yet, the outrage machine means that many of these complainers (some of whom admit to not having seen the film) will get enough attention to make them think they’ve said something worth saying, instead of offering a vapid analysis that many first-year college students would find reductive.