Marilyn, Freddie, Ray, Diana, Jim, Judy, Winston, Lincoln, Elvis – the biopic is a perennial staple of American cinema and the safest bet for Oscar bait you can find. So why are so many of them so incredibly forgettable?

The Academy loves biopics, and so do we

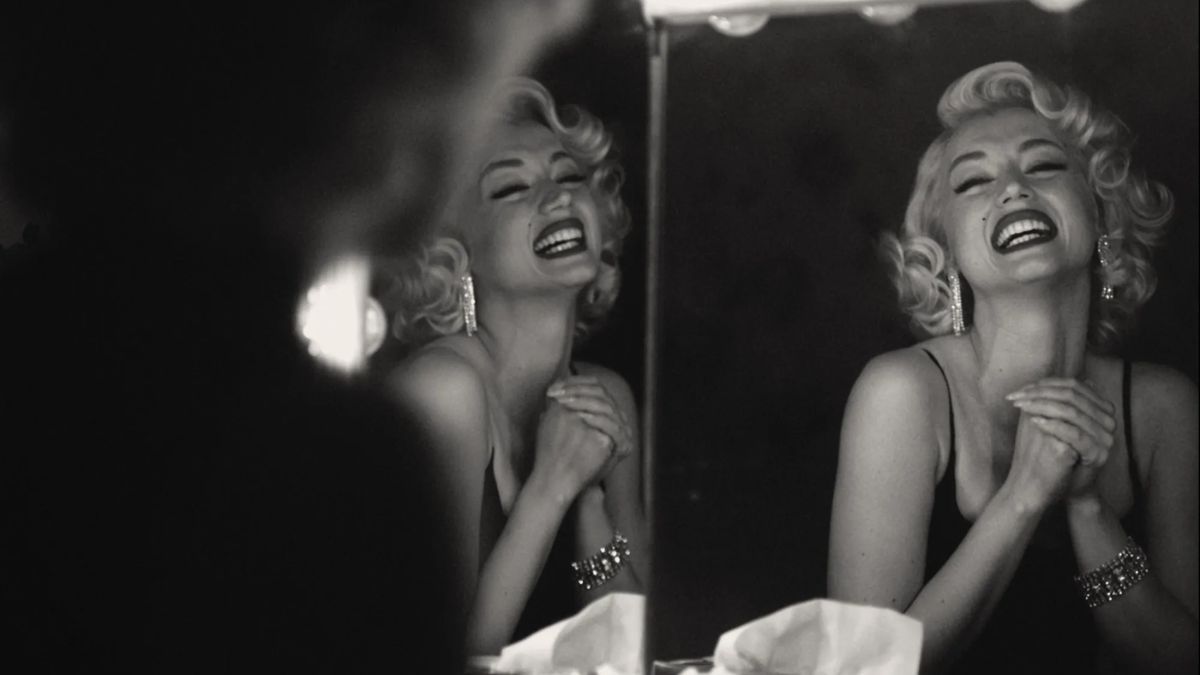

Since the start of the millennium, 32 biographical films have been nominated for Best Picture, and, in 22 editions, 12 Best Actor and 10 Best Actress winners were playing real people. This year, Austin Butler is a big favorite for the award for his rendition of Elvis in the eponymous film by Baz Luhrmann, and Ana de Armas is also nominated for her portrayal of Marilyn Monroe, despite Andrew Dominik’s Blonde being one of the most universally disliked titles of the past season.

Actors jump at the opportunity to play a famous person, to get to embody one of the greats, study their mannerisms and accents. Some keep the accent for years after production wraps. It’s exciting being Elvis for a while. For the Academy, it’s easy recognizing a good performance when you have something to directly compare it to. It’s mathematical, almost.

Audiences are equally drawn to the biopic just on the shared human condition of needing to stick one’s nose in other people’s business, as well as the opportunity to take an exclusive, personal peek at famous events that they didn’t get to live through themselves. The way the genre fits someone’s naturally messy life into a consumable, neat little inspirational package is also highly attractive, selling an idea of meaning and cohesion that often lacks from our own lived experiences.

It’s not hard to understand, then, why every year we’re bombarded with biopics, or why a dozen more are in development as we speak. Especially since the incredible success of Bohemian Rhapsody, studios are collecting dead stars’ life rights like a kid collects sports cards. Both a Michael Jackson biopic and an Amy Winehouse film are currently being developed. Tom Holland is playing Fred Astaire, and Timothée Chalamet is playing Bob Dylan. It’s an epidemic, and for those of us who like to watch every single Oscar-nominated film ahead of the awards ceremony, it’s one that’s hard to escape.

Why are most biopics insignificant?

For all the biopics being frantically produced, only a handful actually become artistically interesting, and even less outstanding. The recent Whitney Houston film I Wanna Dance With Somebody barely made any waves, yet in its structure and style it didn’t differ much from the massively popular Freddie Mercury effort. Did anyone even watch Judy, The Eyes of Tammy Faye, or Being The Ricardos?

Darkest Hour, King Richard, The Theory of Everything, The Danish Girl, The Iron Lady, or The Imitation Game were only okay, but there’s hardly a future where they’re looked back upon as definitive examples of an era of filmmaking. Then there’s Green Book – whose issues far surpass simply being unmemorable.

Blonde, on the contrary, was all everyone could talk about when it dropped on Netflix in September, but for all the wrong reasons. The film — which depicted a highly fictionalized account of Marilyn Monroe’s life under the spotlight — was vigorously criticized for being overly sexual and violent, in manners most deemed disrespectful.

It struck up a debate on the validity of biographical movies about dead people, when they don’t have anyone to stand up for them, and where their famous image is exploited for commercial attention. Fans are already calling for the boycott of Back to Black, the Amy Winehouse biopic, after photos from the set revealed what could potentially be a harmful, sensationalist representation of the British singer.

At the same time, Michael has been preemptively called out for the biased casting of Michael Jackson’s nephew to play the late pop star, the heavy involvement of his estate, and the possible dangers of glorifying a man who might or might not have committed some real atrocities.

Respect vs. beautification

If a biopic goes too into the nitty-gritty of a person’s journey, especially if that person has passed, it can result in unethical, borderline sadistic films like Blonde (and potentially Back to Black). But if it doesn’t dare to touch the controversial, perverted aspects of lives which — being plagued by fame — almost always have a dark side, then they’re cowardly and uninteresting, like Bohemian Rhapsody, I Wanna Dance With Somebody, and possibly Michael. Even Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis very heavily exacerbated and white-washed the famous singer’s interest in the black community and in civil rights, without ever making any actual insightful commentary on how race relations played into his success.

It’s also a fact that, because biopics are focused on this dance around respect and truth — desperately trying to find a balance that will upset the least amount of people — they end up coming out as boring, from a cinematic standpoint. Scripts are generic, stuffed with exposition, and contorted in order to tie erratic events into a classical narrative structure with an emotional climax, and a satisfactory resolution. Additionally, the lack of creative freedom is seldom appealing to imaginative and innovative directors, who struggle to find a fulfilling angle in these stories. Of course, there are exceptions. Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull is perhaps the best biopic ever made.

For all these reasons, any well-intended director who takes on the challenge is essentially setting themselves up to fight an uphill battle. Michael and Back to Black are not off to a great start, but there’s hope. There have been a number of genuinely good biopics in the past, which should serve as inspiration for Michael director Antoine Fuqua and Back to Black director Sam Taylor-Johnson.

The exceptions

Spencer and Steve Jobs (not the Ashton Kutcher film) are incredible movies because they choose to center around one or a couple of pivotal moments in Princess Diana and the Apple boss’s lives, instead of trying to cram an entire lifetime into a couple of hours of runtime. A good script doesn’t need excessive exposition to make you understand its central characters, all it needs is incisive, reflective writing. A good scene can tell you more about a person in a few minutes than their entire life flashing by in fast-paced and superficial sequences.

Rocketman, Love & Mercy, and I, Tonya are fantastic films and a pretty good example of how to bestow depth, sensitivity, and artistic vision to a genre that has become almost as formulaic as superhero movies. In all three movies, the subject of the story was still alive when they were made, which perhaps paradoxically allowed for more freedom than when producers have to contend with the executors of a deceased person’s estate, or, alternatively, close friends and colleagues, as was the case with Queen and Bohemian Rhapsody. Dealing with a dead person’s legacy is extremely tricky territory, because time, mourning, and nostalgia tend to turn late celebrities into myths that are almost impossible to deconstruct. Opting for someone who is still alive and very much human to audiences helps.

David Fincher’s The Social Network, one of the greatest movies of the new millennium — about the creation of Facebook, and which functions essentially as a biopic for its co-creator Mark Zuckerberg — works so well because it is honest and far from flattering. Aaron Sorkin’s script is also perfectly witty and sardonic, fittingly bringing out the uglier sides of its greedy main characters. First Man, At Eternity’s Gate, and tick, tick… BOOM! are other masterful examples on how a biopic can reflect the personality being portrayed through idiosyncratic styles and themes – slow and contemplative, expressionistic and ambiguous, or dreamy and grand.

When dealing with the executors of a deceased person’s estate, creating a movie that might harm the person’s image, from which those executors profit, is almost impossible. However, to go as far as Blonde did crosses lines that don’t just harm, but abuse and exploit a dead person. The goal is to find the middle ground, while occasionally taking creative leaps that are reflective of the protagonist’s genius. You’re dealing with some of the most fascinating subjects and turbulent biographies out there. The source material’s richness is immense. Don’t make it boring.