The name Bruce Lee is still as relevant today as it was 50 years ago.

Despite starring in only four kung fu films during his lifetime, and an additional one posthumously where he appears in about 25 minutes of footage, Bruce Lee is still considered by many as the ultimate martial arts movie star.

His impact on the industry, how we perceive fight scenes, how choreographers design fight scenes, what true charisma means for a martial arts star, and what stories to tell in kung fu films, are still viable today. Of course, how great he was on film is what’s most memorable but it’s also his other achievements and his overall philosophy on life that make him stand out even further.

Bruce Lee broke barriers for Chinese actors by co-starring in The Green Hornet TV series on American television in the mid-1960s. He also taught martial arts to Americans, at the behest of rival Chinese martial arts teachers. He stood for equal treatment and equal opportunities, stating “I want to think of myself as a human being. Under the sky, under the heavens, there is but one family”

Many consider his greatest film — as well as the greatest ever kung fu film — to be Fist of Fury, which was his second overall martial arts movie. The Hong Kong Film Awards, The Golden Horse Awards, and Time Out Hong Kong Magazine all rank it as the best Chinese kung fu film of all time, with the latter two also ranking it among the 20 best Chinese films ever made of any genre.

The movie successfully balances a revenge plot with a racial backdrop while making us all believe in his character’s literal fight against injustice.

Whereas The Big Boss made Bruce Lee a star, it was Fist of Fury that ultimately solidified his stardom and made him a sensation.

Released in 1972, we now look back at the groundbreaking kung fu film 50 years later.

Fearless

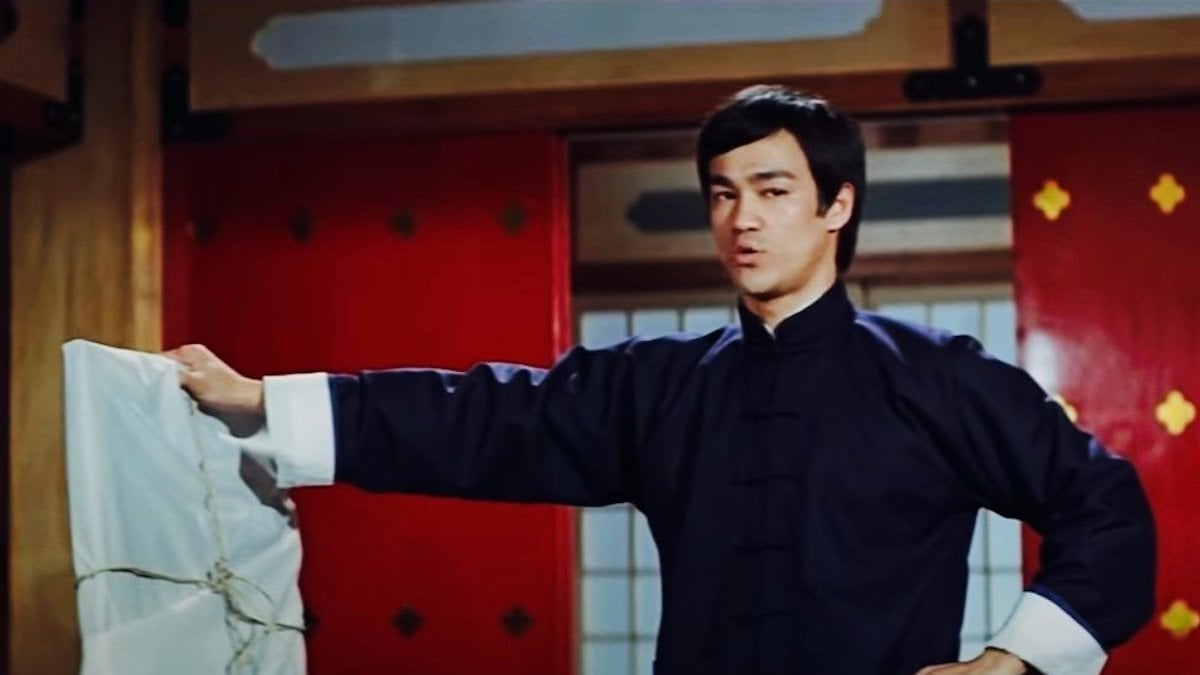

The movie takes place in 1910 Shanghai. From the opening scene, we learn of the death of martial arts teacher Huo Yuanjia and witness his student, Chen Zhen, return to Shanghai just in time for the funeral. We also learn that Chen Zhen, played by Bruce Lee, cannot accept his master’s passing and it becomes obvious that this is going to be a tale of revenge fueled by his emotions.

Huo Yuanjia is not just a character in this film but rather he was a real-life martial arts teacher who was believed to die of sickness with rumors of that sickness being from poisoning by the rival Japanese. Yuanjia’s descendants believe he truly was sick but that the Japanese told him they knew doctors that could take care of him and they ended up intentionally poisoning him instead.

Known as “Fearless”, Huo Yuanjia has been the subject of many kung fu films, including Jet Li’s appropriately named Fearless. Yuanjia didn’t have a student named Chen Zhen but he did have a student named Liu Zhensheng whom Chen may have been patterned after.

The framed drawing depicting Huo Yuanjia in the film that rests in his honor, is an actual drawing of the real life Huo Yunajia.

Sick Men of Asia

The phrase, “Sick Men of Asia,” had first been used in the late 1800’s, mostly popularized by Chinese scholar Yan Fu when referring to the Qing Empire’s failure in the First Sino-Japanese War, which suddenly saw the dominant military prowess of Eastern Asia shift from China to Japan and one can argue ultimately led to the downfall of the Qing Dynasty.

The phrase referred to the corrupted officials of the Qing, who were more concerned with their own personal greed than properly defending China.

“Sick Men of Asia” was then used years later by multiple Russian fighters in Shanghai in their attempt to challenge Chinese martial artists. Huo Yuanjia answered those challenges victoriously.

In Fist of Fury, a Japanese martial arts school offers a gift to the Chinese school following the death of Huo Yuanjia. The gift is a sign that reads “Sick Men of Asia.”

Much like how Russian fighters in real life used the phrase to challenge the Chinese, this depicts the Japanese school using it as an attempt to finally induce one of the Chinese students to fight them, something they have flat-out refused to do since they are taught that martial arts is for self defense only.

However, the insult works. Chen Zhen personally returns the sign to the Japanese school.

In case you’ve seen the film and are curious about the sign itself, the characters are meant to be read right-to-left (a familiar Japanese practice pre-World War I). When spoken aloud in Chinese, the sign reads, “Dong Ya Bing Fu,” and literally translates to “Sick Men of East Asia.”

The legend of Bruce Lee begins

The following scene is one of the more well-known in kung fu film history and one of the most important in Bruce’s career. His character easily defeats 27 Japanese martial artists (yes, we counted) — mostly simultaneously — and the scene introduces nunchuks to martial arts films.

However, it’s also significant for another reason, which is that Lee demanded certain camera angles be utilized in this scene that director Lo Wei reluctantly agreed to. Jackie Chan, who appears in the film as an extra, stated that he witnessed Bruce Lee and Lo Wei nearly come to blows on set over such a disagreement.

Wei had also directed Lee’s first feature, The Big Boss, and this is when Lee became unimpressed with how Wei was portraying the fight choreography, despite Wei being instrumental in Lee getting the starring role over James Tien (who appears in both films). Lee felt his unique realistic style on camera deserved a very unique approach behind it.

Thus, this scene shows camera shots from above the fight scene, below the fight scene — as Lee hits the floor and strikes his enemies’ legs with his nunchucks — and even as part of the fight scene itself as the camera at one point acts like the eyes of the Japanese teacher with Lee looking directly into the camera and striking you, making you practically feel his lightning kicks and making you realize he beats everyone up in this scene including the audience.

After humiliating the Japanese school, he forces their top two students to eat the paper that the words “Sick Men of Asia,” have been written on. Earlier, when first giving the sign to the Chinese school, it was one of those two top Japanese students who said, “If anyone can defeat me, I’ll eat those words.”

A walk in the park

Chen decides to walk off his butt-kicking prowess by taking a stroll in the park, which leads us to perhaps the most popular scene in the film, especially in Hong Kong and China.

Chen is not allowed into the park which is exclusive to the Japanese. A sign at the entrance reads, “No Chinese or dogs allowed.” While the guard stops him, a Japanese man walks in with his dog, prompting Chen to point it out only to be met by another Japanese man who says, “If you want to get in, act like a dog and I’ll take you in.” Of course, Chen responds with his fists of fury — which is actually his character’s nickname in the film — and then, after beating up the man and his friends who laughed at him, Chen destroys the “No Chinese or dogs allowed” sign by kicking it to pieces.

It’s worth noting that Bruce Lee’s stunt double, Yuen Wah, plays the insulting Japanese man.

This scene is the heart and soul of the film, helping emotionally pull in the Chinese audience, who have already delighted at Bruce making the Japanese eat their words, causing them to cheer and roar in approval of their suddenly favorite new movie star.

At the time of the film’s release, Chinese-Japanese relations were still quite complicated, as they were only a generation removed from the Nanjing Massacre. Thus, a movie about a Chinese man defeating the Japanese was guaranteed to be a crowd-pleaser for Chinese audiences.

A national hero

Bruce Lee became a national hero after this film. It broke all box office records in Hong Kong and made him not only the ultimate martial arts film star in China at the time — supplanting both Jimmy Wang Yu and David Chiang — but also made him the most popular movie star in China.

Yet, the film’s success is not limited to a national audience. It became a major triumph internationally as well. It went on to make over $100 million worldwide — an unheard-of sum for a Hong Kong film released at that time — despite a budget of a mere $100,000.

In 1973, it was released in America under a different title because The Big Boss had just been released a month earlier mistakenly under this film’s name. So, to avoid obvious confusion, they released this as The Chinese Connection because a popular movie at the time was The French Connection.

On the heels of Fist of Fury (a.k.a. The Big Boss) being the top box office film in America for one week in May, The Chinese Connection (aka Fist of Fury) became the top-grossing film at the box office for the week of June 13, 1973, just two months prior to the American release of Enter the Dragon.

Bruce Lee’s on-screen charisma along with his character’s indefensible fighting ability helped draw in a worldwide audience, but his character’s fight against injustice also appealed to many. Even just in the context of the film, it’s nearly impossible not to root for Chen to fight back and win.

A fugitive in disguise

Even though Chen’s actions are motivated by his avenging his master’s death, the film understands that what Chen is doing is also wrong. He kills the two people involved in poisoning his master fairly early in the film, including a Japanese cook and a Chinese man played by the senior fight choreographer of the film, Han Ying Chieh – who did all fight scenes not featuring Bruce. This is the famous “Why did you kill my teacher?!” scene which results in Chen hanging the bodies on a lamppost in the Shanghai streets overnight so that the public can see them. He does this again when he kills the translator for the Japanese school — a Chinese man — in a memorable scene where Chen disguises himself as the translator’s rickshaw driver and takes him to a “dead” end where he ultimately kills him.

By this time in the film, Chen is a fugitive hiding out in a cemetery in the woods where he shares a kiss with his visiting love interest played by Nora Miao. A conversation between the two makes you realize that Chen knows there is no turning back now so he decides to keep going until he gets to the head of the Japanese school who ordered his master’s death.

He must go through a seemingly invincible Russian fighter, something of a reference to the Russian fighters who insulted the Chinese and Huo Yuanjia in real life. Chen disguises himself as a telephone man in order to get inside the Japanese school and learn more about this Russian fighter, played by Bruce Lee’s most senior student at the time, Robert Baker (who is actually American).

As expected, the final showdown sees Bruce Lee’s character take on Baker’s and win, only to then immediately go after the head of the school, played by Riki Hashimoto. In typical Chen Zhen fashion, he kills both characters.

And justice for all

It’s almost surreal to watch a kung fu film from 1972 about racial injustice, especially when the star of the film just starts beating up innocent people at one point. However, Bruce Lee understood this and opposed the original ending of the film which saw Chen get away with his crimes. Bruce was adamant that the film must end with Chen’s death because justice should not be a one-sided affair. After all, his character kills a lot of people in the film, many of whom did not deserve to die, but Lee also felt that the movie would be best concluded if Chen dies at least with some honor.

The result is what is seemingly the first kung fu film not to end immediately after the final fight scene (or almost immediately) because the main character’s fate must be played out. It gives further depth to the film, especially since one can appreciate the care that Lee puts into the character’s demise.

Chen returns to his school where the detectives are now hovering and he tells the main detective, played by director Lo Wei, that he will surrender and pay the price for his crimes if nobody else in his school, all of whom are innocent, are not harmed in any way. Upon getting the detective’s approval, they walk out of the front doors together, only to be greeted by police aiming their guns at Chen, who decides to have one last moment of fury but, this time, at his own cost.

The result is the first true kung fu film masterpiece and a movie that’s still praised fifty years after its initial release.

Some see the end of the film as the death of the Chen Zhen character, but we see it as the true birth of Bruce Lee the icon, Bruce Lee the Chinese hero, and Bruce Lee the human being.