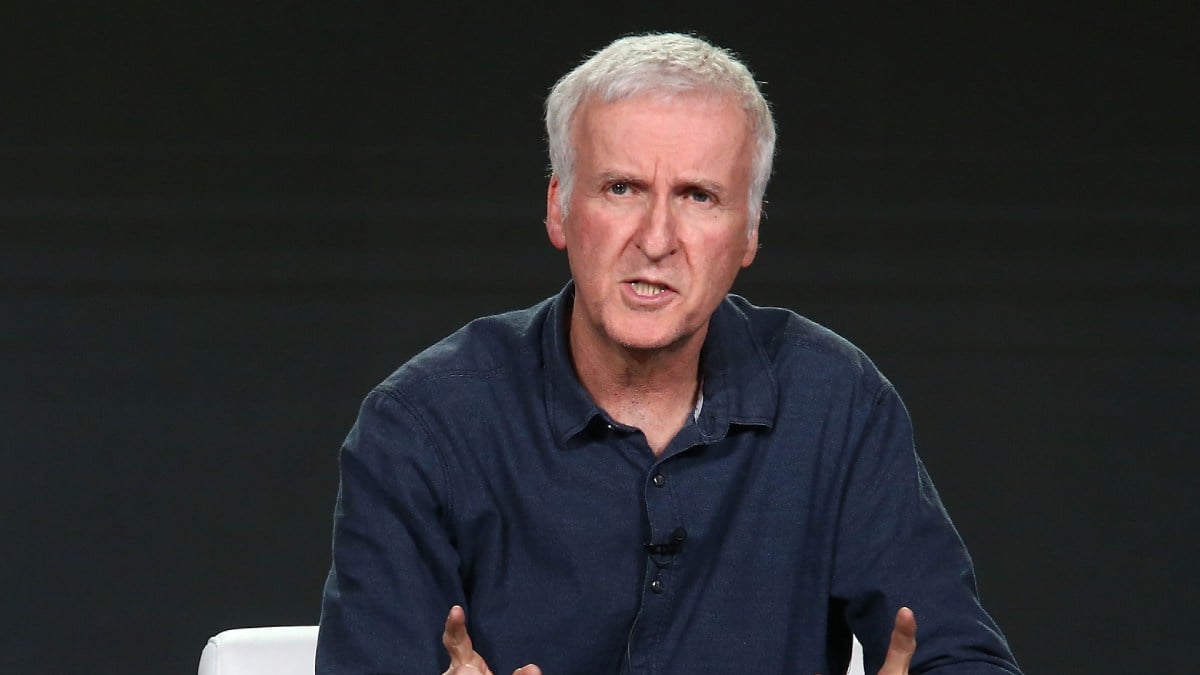

Before we had the Jon Watts trilogy, before the Marc Webb duology, and before the Raimi trilogy … there was an idea. Famed director James Cameron was to make the first major live-action Spider-Man movie. And it was insane.

How James Cameron’s Spider-Man was funded

Spider-Man‘s cinematic rights have been owned by Sony’s subsidiary Columbia Pictures for almost three decades. Before that, the rights were owned by Carolco Pictures, and before that, they were owned by The Cannon Group and legendary Israeli producer Menahem Golan.

Golan, along with Yoram Globus, had built The Cannon Group’s business and reputation by acquiring low-level scripts and transforming them into direct-to-video B movies. In the mid 1980s, the company attempted to produce a live-action Spider-Man film with a catch: if the film wasn’t made by April 1990, Marvel would re-acquire the rights.

The Cannon Group couldn’t make Spider-Man happen, so before the rights transferred to Marvel, Golan and Globus’s company sold the rights to Carolco for $5 million. Carolco had an ace up their sleeve: James Cameron, who co-wrote the screenplay for Rambo: First Blood Part II, wanted to direct the film. But Cameron was also riding high off the success of Aliens and The Abyss, both of which had won and received several Academy Award nominations.

So Cameron wanted a special deal, one that replicated his work on Terminator 2: Judgement Day. Cameron would have the right to decide on movie and advertising credits, which eventually sparked a legal battle in 1993 after Golan sued to regain a credit for producing the film. Carolco, Golan’s new studio 21st Century Film Corp. and Marvel would all go bankrupt three years later, with courts returning the rights to Marvel in 1998 after the company recovered from near-financial ruin.

As for the film itself, the plot was best described as being heavily inspired by the 1990s “dark and gritty” take on comic book characters. It was heavy on profanity and highly sexual, including a rather peculiar sex scene (more on that later). Understandably, the movie got stuck in development hell, although Cameron’s full script treatment would eventually be released online.

The original Spider-Man cast

The titular hero would be played by the most 90s possible casting choice — Leonardo DiCaprio. Fresh off his Oscar-nominated performance in What’s Eating Gilbert Grape, he was hot property for pretty much any studio that needed a lead.

The villains for the piece were meant to be Electro and Sandman, but neither under their traditional names of Max Dillon or Flint Marko – but instead as Carlton Strand and ‘Boyd’ respectively. Electro was to be played by Lance Henricksen, and Sandman by Michael Beihn.

Carlton Strand was written to be a caricature of hardcore capitalist businessmen (think RoboCop), while Sandman was more of a classic Spider-Man villain story of getting involved in mad science experiments involving atoms and the like. Both takes have ended up in later Spidey films, with Sandman debuting in 2007’s Spider-Man 3 played by Thomas Haden Church, and Jamie Foxx as Electro in 2014’s The Amazing Spider-Man 2.

Spidey’s love interest would be Mary-Jane, which did carry over to the Sam Raimi films. Nikki Cox was cast in the role, although she would be later become known for her lead role in the sitcom Unhappily Ever After which ran for 100 episodes. In another treatment for the script, the producers had targeted Arnold Schwarzenegger to play Doctor Octopus, a casting choice that could even work in modern day Spider-Man.

Interestingly, the studio eyed Michael Douglas as J. Jonah Jameson. It’s hard to see someone else in the role after J.K. Simmons’s success. Douglas would eventually appear in the Marvel universe, however, portraying Hank Pym 25 years later in the Ant-Man films. Marvel had also earmarked Kevin Spacey to play Norman Osborn.

The original Spider-Man plot

The plot is fairly standard superhero origin stuff: Spidey is on the receiving end of a tragic event, gains his powers, fights bad guys.

But in Cameron’s version, the spider-bite is decidedly gruesome. He gets bitten and goes through a psychotropic-style trip, something the script describes as “Kafka-esque”.

He awakens from this seizure-like hibernation period with sticky white fluid binding him to his sheets. It’s a blunt puberty metaphor. That’s something the Spider-Man series has always been about, although the comics and future iterations have made that point clear without the imagery of web ejaculation.

Several things from the failed James Cameron version eventually made their way into 2002’s Spider-Man, including: organic web-shooters, a “high-school age” Peter Parker, the on-screen death of Uncle Ben as a direct result of Peter Parker’s mistake.

But what’s most interesting was where Cameron’s vision differed. His version would have been R-rated with frequent profanity, overt sexuality, Electro attempting to sexually assault and an ongoing voyeur-fuelled B-plot. Spider-Man would gain the powers of a male spider, using it to attract female mates including Mary-Jane.

The infamous planned sex scene in particular something that I’m so glad never ever made it to live-action. Taking place atop the Brooklyn Bridge, it taps so deeply into this idea of spider-themed sex. I can’t even properly describe it myself, so here’s the scene as it appears in the script.

Keep in mind, a crucial part of this script is Mary-Jane does not know Peter Parker is Spider-Man during the sex.

Unfortunately for Spider-Man and Mary-Jane, Sandman is a sneaky little voyeur and had filmed them having sex. He sells this tape to the Daily Bugle, but cuts it as Spider-Man abducting Mary-Jane.

The final fight scenes with Electro and Sandman are more interesting with a modern context — the big climax takes place atop the World Trace Centre. This is something that nearly happened several years later in Raimi’s 2002 Spider-Man film, until it was edited out.

Electro dies during the fight, telling Parker the classic “ah you and me, we’re not so different, let’s be mates and do crime together”. Obviously Peter rejects this, but there is one more brilliant bit of dialogue that I would kill to see read by Tobey Maguire’s Spider-Man.

The most amazingly weird thing happens just at the end after the day is saved. Parker and Mary-Jane return to their normal lives at school, their science project gets a B+ grade, all feels good. But when Peter Parker and Mary-Jane kiss at the end – she recognises the kiss. He puts on his Spider-Man voice to confirm to her that he is indeed Spider-Man. It’s fair to say this wouldn’t fly with modern sensibilities, and even by 1990s standards it would have been controversial.

The Cameron script has more bizarre Peter Parker quotes, like this one talking about spiders as Flash Thompson tries to rough him up.

Why Cameron’s Spider-Man was never made

There were multiple issues that stopped Cameron’s Spider-Man coming to life, mainly around financing and the transfer of rights. When The Cannon Group ran into financial difficulties, the studio sold out to Pathe Communications. That company later agreed to sell the Spider-Man rights to 21st Century Film Corp — a company founded by Golan — which itself would later become the center of its own lawsuit, when MGM acquired 21st Century through bankruptcy proceedings.

Production on Cameron’s film also stalled because there were so many script treatments and arguments. Unsurprisingly, an R-rated Spider-Man movie was not expected to sell. Spider-Man is an iconic kids character, a family friendly hero. He’s not The Punisher, and he’s not meant to be sexually charged.

Cameron’s idea was interesting, but interesting doesn’t always translate to commercial success. To me, the best idea was the organic web-shooters. It’s controversial to modern fans but I always like that the webs came with becoming Spider-Man. Otherwise he only has like one actual spider trait to his powers, which is the wall-crawling.

After the Cameron film idea died out, Marvel gained the film rights to Spider-Man in the late 1990s, later selling them to Columbia Pictures which owns the rights to this day.

The Sam Raimi trilogy borrowed some aforementioned smaller ideas from Cameron but it stayed tonally unique, even to other comic book films produced at the time. It had this extremely comic book-y feel and a 1960s charm. They’re timeless films and that’s part of why they’re so good.

James Cameron told the media recently that it was an amazing idea that could have been worth $1 billion to Fox, and that it would be the best thing since sliced bread.

Part of me is so immensely into this twisted, completely plain wrong version of Spider-Man that it does make me wonder if we’ll ever see something this out of left field again for a Marvel character cinematically. And sometimes, the legend of failure and reading these near-misses is more compelling than actually seeing it happen.