Hellraiser is one of the most anticipated horror films of 2022. One of the most striking things about the new film, however, is that the iconic Cenobites have a new look far removed from the leather-clad monsters found in the original films.

This change has a fascinating backstory that touches on how the horror genre and society have changed since the original Hellraiser film landed in theatres back in 1987.

What is Hellraiser?

Hellraiser is a Hulu-original film that acts as a new adaption of Clive Barker’s legendary 1986 novella The Hellbound Heart. This novella was adapted and turned into the first Hellraiser film that landed on screens in 1987 and spawned the popular horror franchise that is still beloved today.

The new film follows Riley (Odessa A’zion), a young woman who finds an ancient puzzle box and becomes obsessed with it. When using the box, however, she ends up summoning monsters from another dimension who are desperate to fulfill their purpose.

Why do the new Cenobites look different?

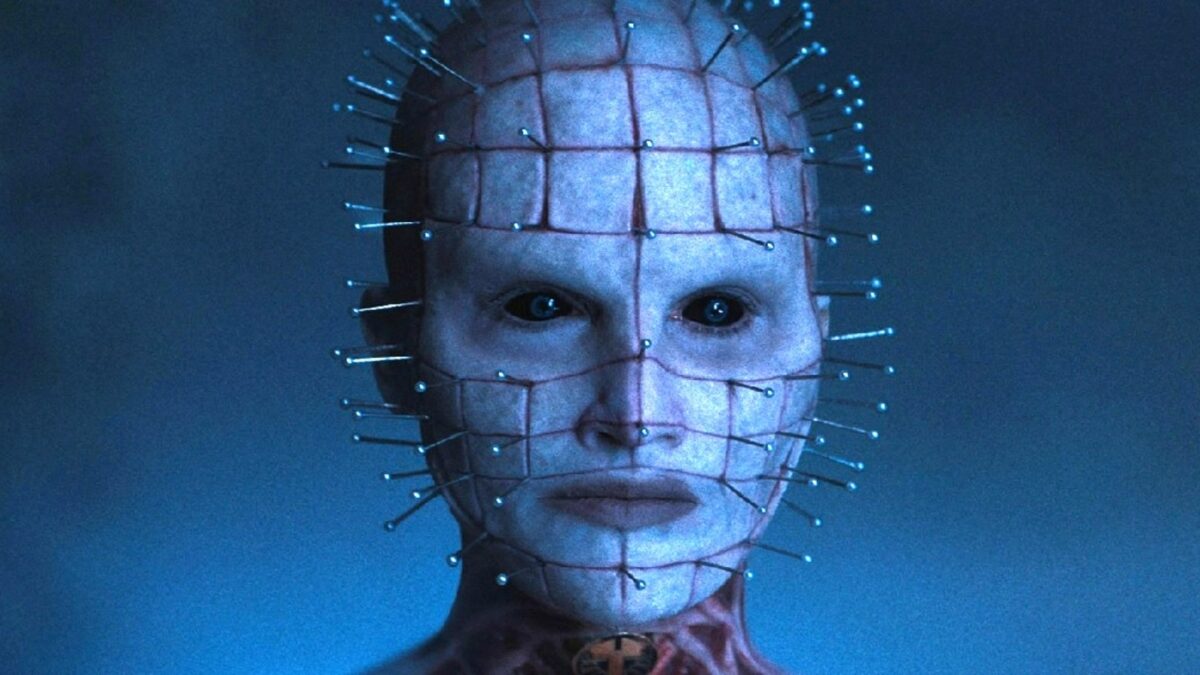

In the original version of Hellraiser, the Cenobites are clad in black leather or PVC, with many of them accessorizing their outfits with spikes and chains. The Cenobites found in the new movie have a sleeker, almost biomechanical look. During a Q&A at Fantastic Fest, the film’s director David Bruckner explained this change.

It’s very popular right now to reproduce the things we love from our youth in a very exacting fashion. But for me, I just couldn’t help but imagine what it must have been like to see Cenobites for the first time…and in exploring that we just felt like our attitudes, on you know, that direct of a BDSM reference had kind of changed.

Bruckner also noting that the black leather look was no longer “as transgressive as it was in the 80s” before adding: “You know, we can talk about it, it’s a culture, the time communication. My mom’s reading 50 Shades like, it’s just, it’s just a different time. Bruckner also wanted to create Cenobites that “captures that unpredictability that offensiveness but still feels very Hellraiser.”

He then explained the new designs by walking attendees through the design process. With him asking what it would be like if “Cenobites could pursue all of their delights, and not necessarily be tethered to a kind of earthly subculture.”

Bruckner says his team “started thinking about extreme body mod” and “what we could do with modern-day resources.” Before they “stumbled upon this idea of like, what if they were their own bladder, you know, what is leather, but a representation of flesh and skin.” Perfectly explaining why these new Cenobites look so different from the older ones.

It’s hard to disagree with Bruckner. Even long-time Hellraiser fans will admit that the original Pinhead design isn’t as shocking as it once was, since years of pop-culture ubiquity and parody have dulled the impact quite heavily.

Clive Barker’s stories were heavily influenced by the underground queer and kink scenes present when he wrote The Hellbound Heart and other contemporary tales. The best example is 1990’s Nightbreed, a film based on Barker’s book Cabal, written two years after The Hellbound Heart. Like Hellraiser, Barker directed this movie and wrote the screenplay.

Nightbreed follows Aaron Boone (Craig Sheffer), a man who finds Midian, a city where monsters are accepted. He must then defend this city against the police officers keen to destroy it and wipe out the city. Nightbreed has become a cult classic, and many fans and film historians point to the film’s overtly queer subtext. Like the Cenobites from Hellraiser, the monsters in Nightbreed obviously pull design details and cultural signifiers from the queer and kink communities that existed in the 1980s. In fact, once you start to make your way through his work. These themes are inescapable.

As Bruckner notes, these elements have become less taboo in society, and the existence of BDSM and its related subculture is no longer an obscure thing only talked about in hushed whispers. The aesthetic launched by this subculture has become basically mainstream, with many musicians and designers taking elements from the style and working it into their designs.

The most obvious example of this change is the recent conspiracy theory about British Prime Minister Liz Truss’ choice of neckwear. The fact that this alleged symbolism is common enough for a massive chunk of the internet to pick up on it independently. That a lot of media is covering it as a silly internet meme rather than a lurid scandal shows that the subculture is much more prominent and known than it was in the 1980s.

When Hellraiser first hit screens in 1987, many reviews noted its more adult nature with a mixture of confusion and disgust. The Washington Post’s Richard Harrington described the picture by saying:

It’s a decidedly adult picture, with some disquieting sexual tensions that simply wouldn’t work with the usual teen crew.

The Chicago Tribune’s reviewer took it one step further, noting that:

The supernatural arrives, not to reinstate the traditional family model as in Spielberg’s films but to inject an extra dose of sexual anxiety.

Both of these reviews feel delightfully quaint when looking back at the film with a modern eye. Especially as many later films have taken horror and sex scenes in movies to further extremes and been highly praised for it. Today Pinhead, the most iconic Cenobite, looks like your average backup dancer at a Lady Gaga concert.

So it is easy to see why David Bruckner changed the Cenobites to make them more shocking. Like the movie industry itself, transgressive subcultures are always changing and evolving, constantly reacting to the world around them. So to remain transgressive, you must move forward.