When Justin Baldoni optioned Colleen Hoover’s 2016 novel It Ends with Us for a feature film in 2019, the book had sold over one million copies and had been translated into 20 different languages. Then TikTok came along, propelling the book to the summit of multiple bestseller lists and putting it on everyone’s radar.

That much popularity meant scrutiny was unavoidable, and when you consider that the book deals with domestic violence, that scrutiny is multiplied by a significant factor. Everybody talking about your book is great for sales (to say nothing of the importance of domestic violence discussions), but those yet to read Hoover’s novel (guilty as charged) might be put off from doing so due to this controversy. They may, in turn, carry similar feelings for the film adaptation.

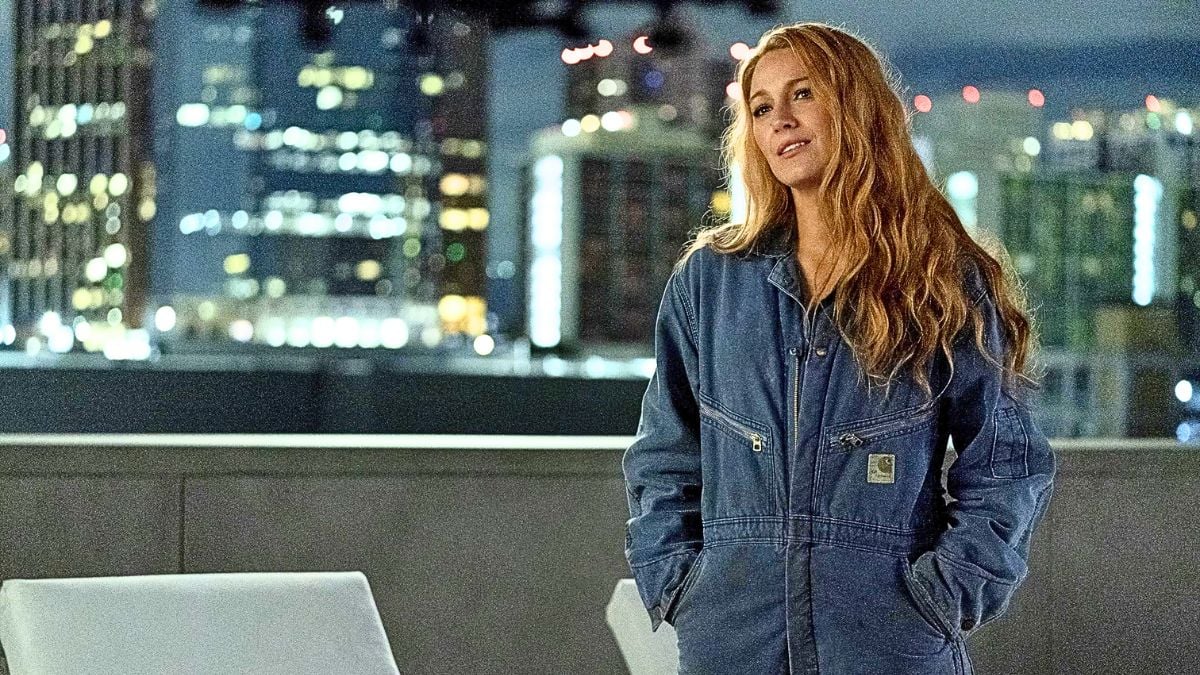

They should brush those feelings aside, because It Ends with Us fires on all the cylinders that matter, and then some. An iridescent Blake Lively gracefully leads this compassionate, smartly-styled adaptation, and Baldoni’s direction gives the movie an artistic heft that shouldn’t be slept on. It creaks on more than a few occasions, but those are easily forgivable mistakes in the grand scheme of It Ends with Us (though it cannot and should not receive any pardon for the wet eyes that it will likely cause).

The film stars Lively as Lily Bloom, a florist who moves to Boston to start a new venture as a flower shop owner. Here, she runs into Ryle Kincaid (Baldoni, also the director), who takes a particular liking to Lily, which Lily eventually reciprocates. Also in the Boston area is Atlas Corrigan (Brandon Sklenar, who underplays his character beautifully), Lily’s high school boyfriend who suddenly fell out of her life when they were young. In case the film’s title doesn’t give away the rest of the film’s synopsis, Lily and Ryle’s relationship is exciting, loving, and everything Lily could ever hope for, until it very much isn’t.

Let’s get one thing straight: It Ends with Us does not romanticize domestic violence. It paints Ryle in a sympathetic light, it is unwaveringly committed to love, and it is a complex, messy, scary, and beautiful story. But, it never justifies or romanticizes domestic violence in any way, shape, form, or fashion.

This is because Lively steps into Lily Bloom’s shoes in a way that paints the movie with her mortal essence. From the moment Lily’s experience with domestic violence is subtly established at her father’s funeral, Lively is a kaleidoscope of gentle power throughout. Through her, audiences will have no trouble believing that Lily is prone to great joy and humor, and also vulnerable in the way that anyone who must fight against their natural way of being will recognize. Lily loves to love without limitation, and in a perfect world, we could all do so.

So while some may become frustrated with some of Lily’s choices, her arc is absolute and revolutionary. The film wants us to understand that it’s possible to cheer for Lily’s commitment to love while also cheering for the removal of the abuse that she suffers at the hands of Ryle. It excuses none of Ryle’s behavior, but instead poses the question of who’s going to be responsible for all of this love that everybody apparently deserves. The answer isn’t “Lily,” but she wants it to be, and she just has to learn how to do that safely, if she can at all. In this way, the film issues a benevolent ultimatum; there’s no law against absolving ourselves of the duty to take care of each other, but we’d be wise to not underestimate our capacity for making the world better.

Speaking of Ryle, Baldoni’s great in the role, but his direction stands out as his strongest contribution by a marked distance. He frames Ryle’s physical abuse (most notably, the instance where he first hits Lily, and the one where he pushes her down the stairs) as ambiguous events, which lends a chilling nod to the nature of domestic violence. They’re depicted as blurry, lightning-quick moments that the camera can’t process, and we’re left wondering what exactly happened.

Except, we’re not. We know exactly what happened, and if the choice had been made to not later show these events as they actually happened, it would have been even more effective. Nevertheless, that clarity works thematically and narratively, and the initial sequences have already done their job by then.

Shockingly, that’s not even the most interesting aspect of Baldoni’s direction. This honor goes to the very light rom-com set dressing that It Ends with Us plays host to. In the rom-com-like scenes, Christy Hall’s screenplay reads like an above-average genre exercise, but the way Lily and her friends bounce in and around the dialogue plays a substantial role in creating that atmosphere; an atmosphere that owes itself to the direction of these already-great performances. Thanks to this, the film is given necessary levity; not enough to cause a complete gear shift, but enough that we remember the hope that Lily represents and has access to.

Moreover, these rom-com stylings very much lean into the overarching sentiment of It Ends with Us. Rom-coms have a reputation for being a safe genre that emphasizes comfort-viewing, and if there’s one thing that It Ends with Us champions more than love, it’s safety. Safety is both the armor and the tool that love – the type of love that Lily values so deeply, and that we should all value so deeply – needs to thrive in a complex world; this is Lily’s odyssey.

If It Ends with Us finds box office success akin to its source material’s sales numbers, it will have earned every penny. Hall’s script and Baldoni’s direction combine to buoyant effect, even if the on-the-nose storytelling is, at times, too close for comfort. But then, It Ends with Us isn’t supposed to be a comfortable film. It wants us to radically compartmentalize our ideas about love and relationships, and it wants us to do so with steely compassion. These are important, powerful, and utterly respectable intentions that stick the landing, and with Blake Lively as its landing gear, It Ends with Us does very little wrong.