Long before we hit the summer months, 2024 had already made it abundantly clear that it wanted to spoil us rotten in the blockbuster sphere; between Dune: Part Two, Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire, The Fall Guy, and Kingdom of the Planet of the Apes, audiences of all predispositions have been anything but starved of spectacle, scope, and unadulterated fun this year.

It appears that Twisters, incidentally billed as a contender for this summer’s defining cinematic event (a title we all know preemptively belongs to Deadpool & Wolverine), is instinctively aware of the pristine hospitality that its blockbuster brethren has been serving up. This is because the film has made the confounding decision to play itself as tamely as its premise could conceivably allow, as if it somehow didn’t have the confidence to stand alongside its fellow popcorn films the way it was largely expected to.

Indeed, piled under the howling winds of Twisters‘ stormy ordeal is some semblance of thoughtful heart, and Glen Powell continues to prove himself as free cinematic nutrition no matter the project, but it unfortunately commits the great sin of trying too dang hard to please everybody; so much so that screenwriter Mark L. Smith and director Lee Isaac Chung seem to have forgotten to include (or worse yet, value) their own voices here.

The film stars Daisy Edgar-Jones as Kate Cooper, a once bright-eyed storm chaser who devises a special chemical solution designed to disrupt tornados, hoping to use her invention to prevent future natural disasters. A traumatic accident/mistake puts her off the practice indefinitely, but she’s tracked down five years later by her friend Javi (Anthony Ramos), who hopes to enlist her expertise on storm chasing to implement state-of-the-art tornado tracking technology in Oklahoma, which is experiencing a once-in-a-generation tornado outbreak. Also chasing the storms is YouTube sensation Tyler Owens (Powell) and his crew, and the two groups wind up in a deadly battle against Mother Nature as they fight for their own survival, and that of local townsfolk.

Let’s not kid ourselves here; no one is walking into Twisters expecting any sort of cutting edge pathos or intimate character drama. They’re walking into Twisters to watch big blowy weather do big blowy weather stuff (most of it loud, destructive, and exciting). With sole respect to that bar, Twisters does fine; the tornado sequences do offer up an impression of a towering, adversarial force, and the sequence in which a vortex touches down in the middle of a rodeo (roughly halfway through the film) is a genuinely harrowing and well-crafted one. The latter especially is an undeniable plus of Twisters, but unfortunately, it also highlights how lacking the film is on so many of its other presentational fronts.

For one thing, it wouldn’t be outrageous to say that Twisters is severely dissatisfied with itself whenever it has to toss us some scenes that don’t involve high-octane tornado action. Indeed, such in-between moments are filled with tornado jargon that offers exactly one (1) blink-and-you’ll-miss-it instance of narrative mileage, and dialogue/character interactions that could not be less charming if they tried (it’s perhaps a good thing, then, that script didn’t seem to try). This character-development shortfall is far-and-away the film’s biggest weakness, as it makes it impossible for us audiences to connect to these characters emotionally, which means there’s not really anything for the spectacle of Twisters to root itself in. The resulting tension is deeply, shoddily manufactured; the kind that will only get someone’s heart racing if this is their first time ever watching a movie.

That brings us to Lee Isaac Chung, whose direction makes a too-similar mistake that Smith did with his script. Just as the dialogue seems to just fill up the space for the sake of filling up space, Twisters is in far too much of a hurry to show itself off to well and truly take advantage of its spectacle potential. Chung did a fantastic job with the aforementioned rodeo sequence, but a better version of the film would have taken notes from its use of long takes, intimacy with disaster, and its protagonists very visibly and laboriously contending with duress; all tried and true tools of the Cameronian and Spielbergian set pieces of yore. Why, then, are we given so fewer luxuries elsewhere in the film? Why all the quick, shaky shots of things falling over and people being hurried into buildings? Why neuter the sense of scale for the sake of making more noise? We know that Chung, from that aforementioned rodeo sequence alone, is more than capable of making great spectacle, but after watching Twisters in its entirety, one has to wonder if the director himself is aware of that.

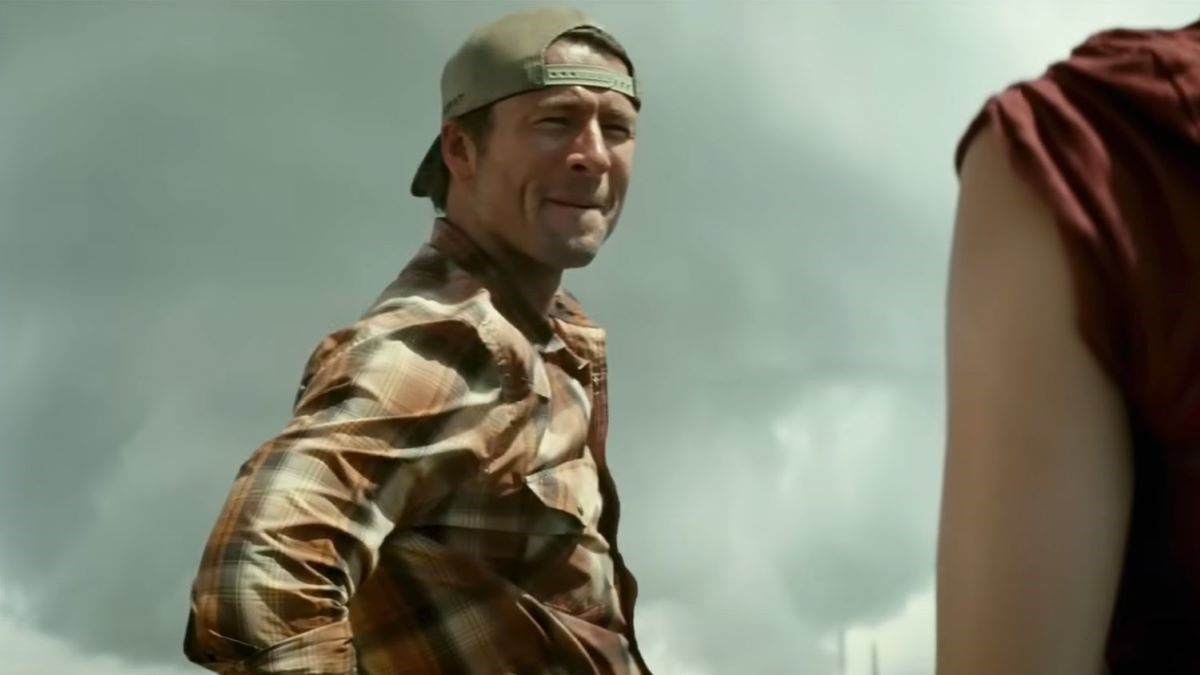

But there is one aspect of Twisters that’s sure of itself, and, to nobody’s surprise, it’s Powell. Indeed, the modern-day movie star is perfectly cast here. Tyler Owens, at a glance, is the ultimate douchebag; cocky, loud, and with an ego seemingly the size of Tornado Alley itself. These types have been firmly established as Powell’s bread and butter (see: Anyone But You and Top Gun: Maverick), but in the context of Twisters as an idea (which is different from Twisters as an end result), it’s a character he inhabits intriguingly.

There’s something to be said about the way all of these characters interact with the storms; to understand them, to profit off them, to learn how to stop them, and everything in between and beyond. Tyler, who Powell loans a sort of mythological sheen to, chases tornados simply because he must chase them. His interest lies not in bringing the tornado down to his level, nor rising above it; he wants to stand toe-to-toe with Mother Nature’s deadliest weapon and stare it in the eye, because that’s his nature. The fact that it’s also in his and his crew’s nature to help those who have been impacted by tornados is no accident, either; Tyler is recklessly human for the sake and joy of being human, and it’s honestly a shame that Twisters, in its parts and in its sum, didn’t show even of a fraction of this sort of interest in Tyler, especially since Powell put it all on such a finely-chiseled plate.

All in all, Twisters just isn’t brave enough to rise to any sort of notable occasion whatsoever; the film’s characterization is painstakingly people-pleasing and wooden, and its cinematic high points were very firmly in the minority (despite possessing a very noteworthy high point). And while Powell may be a great weapon in any filmmaking arsenal, it’s all for naught if you approach your mission objective with the meekness that Twisters did. But hey, at least there’s big blowy weather.