By now, everyone and their mother has seen the latest true crime biographical series from Netflix’s Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story. It seemed to become an overnight sensation, sparking discourse online, starting important conversations and generating praise for its flawless storytelling and particularly Evan Peters’ performance as the titular serial killer.

As identified over time, the key component that allowed Jeffrey Dahmer’s reign of terror to continue was the societal neglect from a racist and corrupt justice system. Rather than making it their mission to defend minority communities, a majority-white police force allowed Dahmer to torment and murder 17 young men and boys between 1978 and 1991. It has been noted through documentation and recounts of Dahmer’s murder spree that he could have been apprehended multiple times prior to his eventual arrest in July 1991.

While Dahmer is the unfortunate namesake of the series, Niecy Nash has earned international recognition for her portrayal of Glenda Cleveland, Jeffrey Dahmer’s next-door neighbor at the Oxford Apartments on North 25th Street, where he committed most of his murders. In real life, Glenda Cleveland lived in the building adjacent to the Oxford Apartments, while Pamela Bass was Dahmer’s next-door neighbor. Despite living in another building, it remains true that Glenda was the individual who informed authorities of Dahmer’s behavior. It was she that called the police after spotting Konerak Sinthasomphone, one of Dahmer’s youngest victims at just 14, stumbling out of Oxford apartments, apparently drunk.

Glenda Cleveland, along with the local community of Black and brown residents, assisted in Dahmer’s eventual incarceration. Throughout history, some of the world’s most notorious serial killers have terrorized neighborhoods for sometimes years on end. However, just like Glenda Cleveland, Pamela Bass and their fellow Black Americans, there are other marginalized communities who wouldn’t stand for a murderer on the loose in their hometown.

1. Moms of murdered children in Atlanta formed S.T.O.P., unsatisfied with Wayne Williams as sole suspect

Especially covered in James Baldwin’s 1985 novel The Evidence of Things Not Seen, the Atlanta murders of 1979–1981, often called the Atlanta Child Murders, were a horrific string of murders targeting at least 28 children, adolescents and adults in Atlanta, Georgia, between July 1979 and May 1981. While the identity of the murderer has never been confirmed, Atlanta native Wayne Williams, a music promoter and freelance photographer who was 23 at the time, was arrested for suspected involvement. He was subsequently tried and convicted of two of the adult murders, for which he received two consecutive life terms. However, the child murders were never solved.

Williams, who claims he was en route to an audition to scout a female singer, found himself questioned by a skeptical police patrol. He insisted that the woman’s name was Cheryl Johnson, who Williams claimed lived in the nearby town of Smyrna. Police found no record of Cheryl Johnson nor their arrangement. As suspicious objects turned up in Williams’ car, it came to the attention of all those involved that he had handed out flyers in predominantly Black neighborhoods calling teenagers and young adults between 11–21 to audition for his new singing group, which he called “Gemini.”

Camille Bell was the driving force behind the Committee to Stop Children’s Murders. Her son, 9-year-old Yusuf Bell, was found dead on Nov. 8, 1979. Bell’s body was found in an abandoned school building. It was Camille Bell who led the other mothers of the murdered children to become an advocate for justice in her predominantly Black neighborhood. In August 1980, Camille Bell and seven other mothers formed the Committee to Stop Children’s Murders with Bell as its chairwoman. Bell and the others took matters into their own hands, reaching out to various news outlets and following trails to hopefully track down the culprit.

Since Wayne Williams was never charged with the murders due to lack of evidence, it left the community unsatisfied. Although her son’s murderer was never determined, Bell tirelessly organized the fight against ignorance to force authorities to prioritize the deaths of Black youths.

Williams is currently serving his sentence at Telfair State Prison in Telfair County, Georgia.

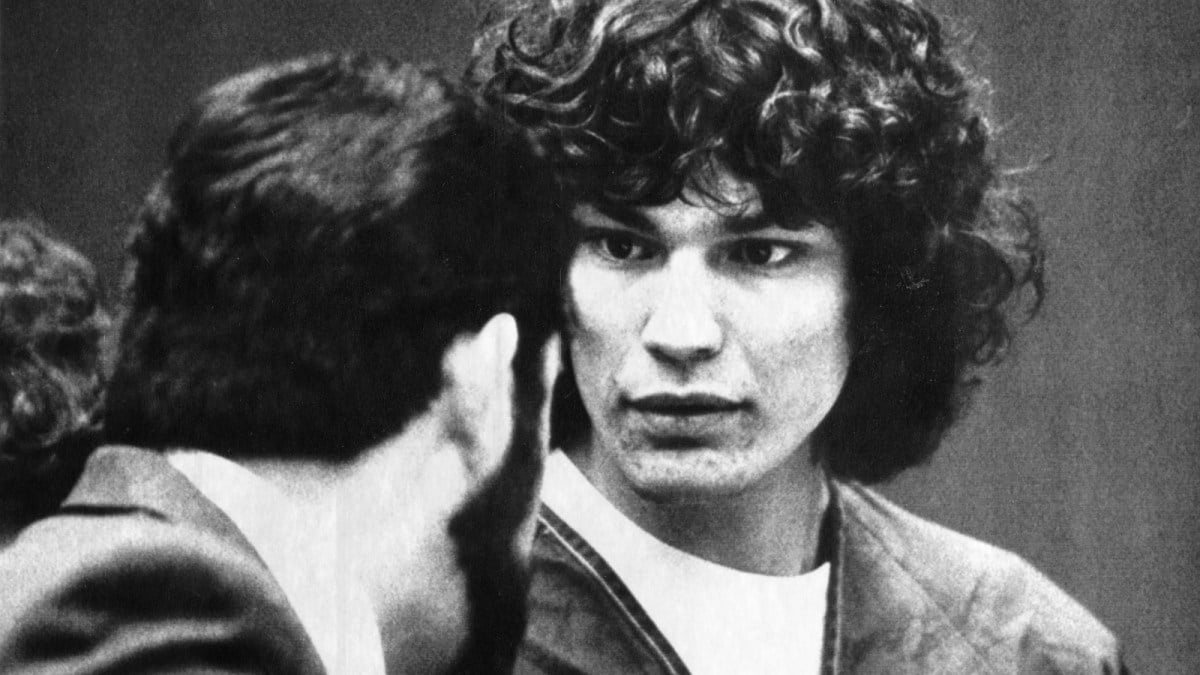

2. Richard Ramirez is apprehended in East L.A. neighborhood

Perhaps one of the most famous cases of all time, Richard Ramirez, dubbed The Night Stalker, operated in California between June 1984 and August 1985. His first cluster of kills took place in San Gabriel Valley, earning him another nickname: the Valley Intruder. The highly publicized home invasion murder spree targeted victims in Greater Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area, wherein Ramirez raped, murdered and/or assaulted several individuals and couples. In 1989, Ramirez was tried for 13 murders, five attempted murders, 11 sexual assaults and 14 burglaries for all of which he was found guilty, resulting in a death sentence.

In August 1985, Ramirez took a bus to Tucson, Arizona to visit his brother, who wasn’t home. After spotting a police patrol and ducking into a convenience store, Ramirez saw his headshot on a local newspaper with the caption “Invasor Nocturno” (Night Invader). He fled the store, attempting hijack the car of a bystander and was struck over the head with a fence post by Manuel De La Torre, the husband of Angelina De La Torre, whom Ramirez had tried to rob. Shortly thereafter, enraged residents from the East LA neighborhood formed and chased Ramirez down Hubbard Street in Boyle Heights, subsequently catching and beating him until police arrived on the scene. The East LA neighborhood has no idea who Ramirez was until whispers of “el matador” (the killer) made their rounds through the crowd. It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that without the combined efforts of the local community, The Night Stalker might have continued his reign of terror for many more years.

Ramirez died from complications caused by B-cell lymphoma on June 7, 2013, never making it to his execution on California’s death row.

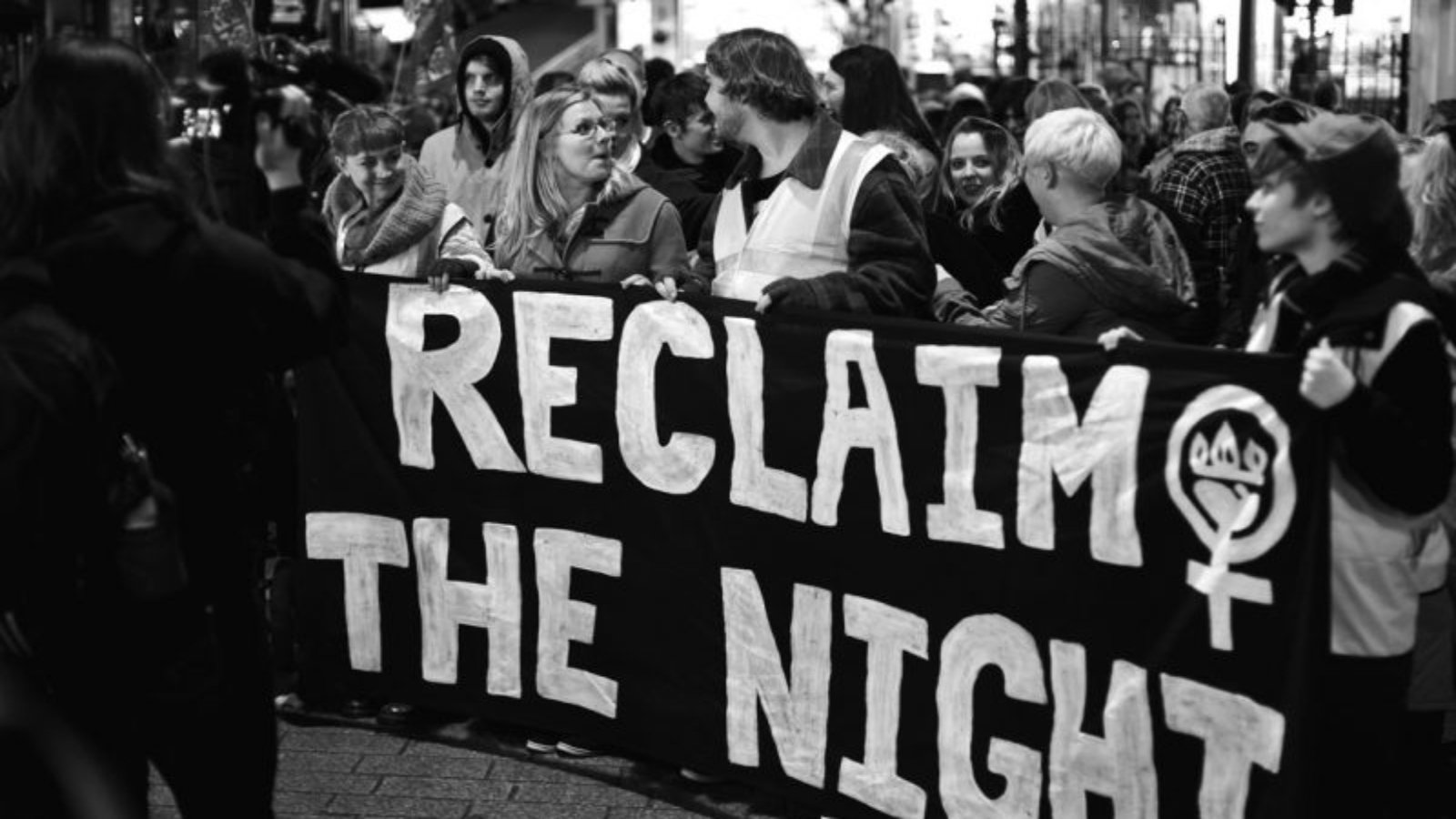

3. Mass “reclaim the night” protests by women in response to Yorkshire Ripper and botched investigation

Dubbed the Yorkshire Ripper by multiple press outlets, Peter Sutcliffe was found guilty of murdering 13 women and attempting to murder seven others between 1975 and 1980. Much like Jack The Ripper’s crimes, Sutcliffe would target prostitutes, whom he claimed “God” had sent him to kill. Despite having interviewed him nine times in the course of a five-year investigation, West Yorkshire Police were criticized for their failure to catch Sutcliffe, which could have ended the killing spree a lot sooner, a lá Jeffrey Dahmer.

The Yorkshire Ripper was arrested in Sheffield by South Yorkshire Police for driving with false number plates in January 1981. When questioned about the murders, Sutcliffe confessed. In the aftermath of his arrest, trial and sentence, police responded by instructing women to stay out of public spaces after dark. In retaliation, a movement called Reclaim the Night started in Leeds in 1977. Part of the Women’s Liberation Movement, the participants orchestrated marches across England until the 1990s that demanded women be able to move through public spaces at night — safely and without fear.

In 2021, Reclaim the Night Leeds tried to stage a vigil in response to the death of Sarah Everard, a 33-year-old who was kidnapped in South London, raped, strangled and her remains burned. The protest turned virtual after police enforced in-person restrictions to regulate COVID-19. Over 28,000 people attended Everard’s online vigil, which was streamed across Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

On Nov. 13, 2020, Sutcliffe died from COVID-19-related complications in hospital while in prison custody. He was 74 years old.

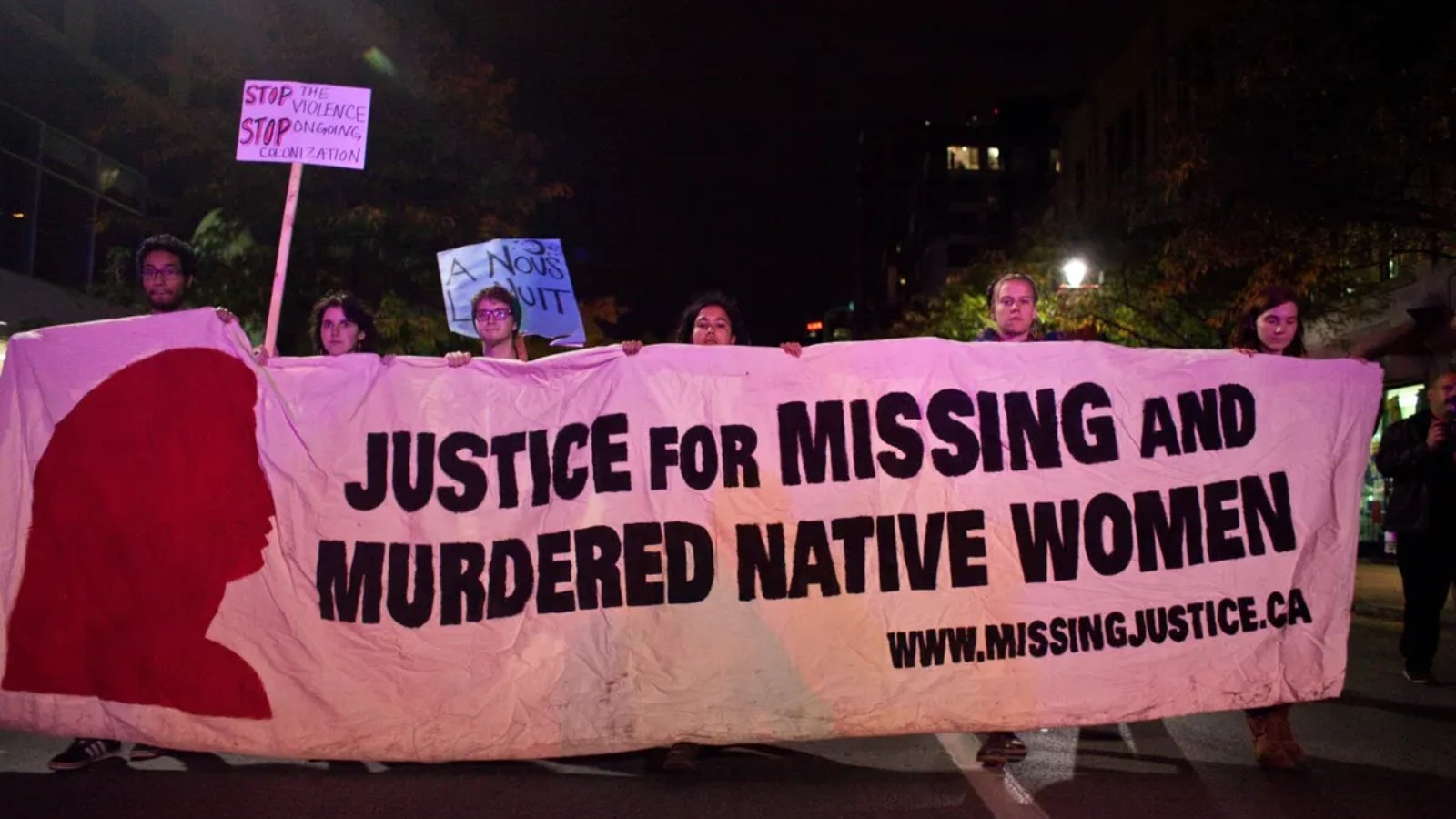

4. “Highway of Tears” murders and the rise of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Movement

Beginning in 1970, the 725-kilometre (450 mi) stretch of Highway 16 between Prince George and Prince Rupert in British Columbia, Canada, has been the geographical location of many disappearances and murders. It was named the “Highway of Tears” by Florence Naziel, who coined the phrase after thinking of the victims’ families crying over their loved ones. It has become common knowledge that a disproportionately high number of Indigenous women appear on the list of victims. Accounts vary as to the exact number of victims. Some researchers find there to be less than 18, while others estimate the number of missing and murdered women to be as high as 40. There have been arguments that a lot of these unsolved cases are the result of systematic racism against Indigenous women, who are frequently the victims of femicide.

Besides the Highway of Tears, the 49 women from the Vancouver area murdered by serial killer Robert Pickton is also considered to be a notable case. According to statistics: “In the US, Native American women are more than twice as likely to experience violence than any other demographic. One in three Indigenous women is sexually assaulted during her life, and 67% of these assaults are perpetrated by non-Indigenous perpetrators.” The Native Women’s Association of Canada is one of many organizations at the heart of the movement, which fights to end violence against Indigenous women. In addition, community-based activist groups “Families of Sisters in Spirit” and “No More Silence” have been compiling the names of missing and murdered Indigenous women since 2005. In 2016, the Canadian government recognized an annual day of remembrance, marked by the Vancouver march, wherein the committee and public would stop at the sites where the women were last seen or known to have been murdered, then hold a minute’s silence out of respect.

From 2017 onwards, the event was held annually on Valentine’s Day in more than 22 communities across North America. In solidarity with the victims, land defenders use red dresses, red handprints, and other references to the MMIW movement to rouse direct action and raise awareness about violence against Indigenous women.

5. Two investigative journalists seek justice for the missing women of Juárez

Deemed the femicides in Ciudad Juárez, an estimated 370 women were killed between 1993 and 2005 in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. Due to the inaction of the government in bringing the perpetrators to justice, the murders of the women and girls received international attention. Many of these deaths were attributed to robbery, gang wars, sex trafficking and sexual assault. While it seems over 400 women have been reported missing or murdered, many investigations have been inconclusive. Especially as more cases are swept under the proverbial rug, authorities have been accused of conducting rushed investigations with questionable methodology and integrity. In fact, many suspects have been allegedly tortured into confessing, which has caused uncertainty of the legitimacy of investigations and convictions.

Numerous local efforts have helped draw attention to the missing and murdered Juárez women; a group of feminist activists founded Casa Amiga, Juárez’s first rape crisis and sexual assault center, in 1999; a social justice movement named Ni Una Mas, which in Spanish means “not one more,” was formed to raise awareness for the femicides in 2002; and a family-led, non-profit organization called Nuestras Hijas de Regreso a Casa A.C. (“Our Daughters Back Home” in Spanish) also formed to tackle the injustice towards the femicides in Juárez.

Ortiz Uribe, a professional journalist, has worked in El Paso as a border correspondent for several public radio outlets, including PRI’s The World. She investigates drug violence, immigration, and the hundreds of femicides that have plagued Juárez. In Uribe’s podcast, Forgotten: Women of Juárez, which premiered in June 2020, she and her co-host Oz Woloshyn delve into the decades-long murders.

When interviewed by Texas Monthly about her reasoning behind the podcast, Uribe responded that she felt obligated to tell the stories of the deceased.

I was so struck when I first learned about the murders, because I didn’t see much difference between [the victims] and me. I lived north of the border and they lived south of the border, and yet there was this huge chasm between our lives. I had all of these opportunities that they didn’t. I felt like I had a responsibility to them that I still feel to this day: to use the privileges I had to tell their stories.

While watching and enjoying Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story, we implore viewers to keep in mind that the killings depicted are based on real events and many young men lost their lives to the monstrous Milwaukee Cannibal.