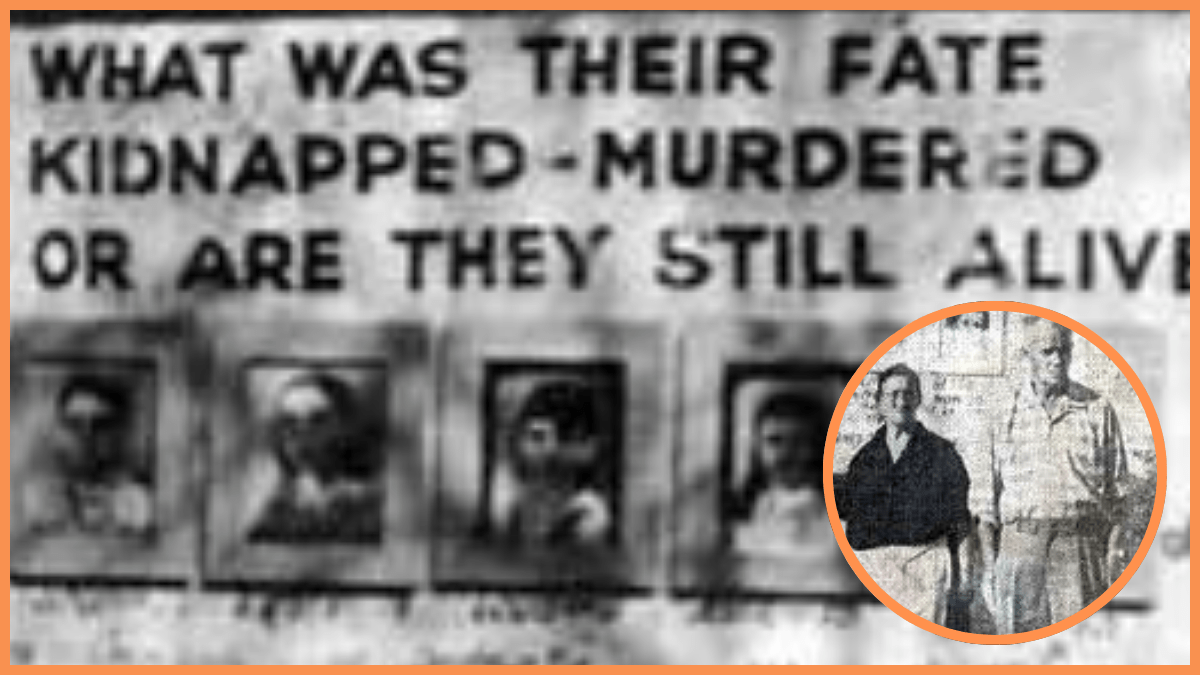

In 1952, George and Jennie Sodder erected a billboard near Fayetteville, West Virginia, where they lived. The faces of five of the Sodder’s 10 children, rendered in haunting black and white, peered out from the sign, which stood in place for nearly 40 years, when Jennie died.

Seven years before that billboard was put up, the Sodder family home burned to the ground on Christmas Eve of 1945. George and Jennie and four of the Sodder children escaped the inferno, but despite George’s valiant efforts to save five of his children, Maurice, Martha, Louis, Jennie Jr., and Betty, never escaped the top floor of the house. When the blaze happened, one of the Sodder’s 10 children was away in the military.

On Christmas Day, 1945, it was assumed that the remains of the five missing children, who were between 5 and 14 years old, would be found amongst the ashes of the Sodder family home. Fragments of bone and organs were uncovered in the preliminary search, but there were nowhere near the quantity or types of remains authorities thought they might find.

The missing children were officially ruled dead from the fire or suffocation, and faulty wiring was what caused the blaze, according to the investigation. And four days after his house burned down, George — distraught — bulldozed dirt over what remained of his home. But based on a series of mysterious circumstances, the Sodders were never convinced their children were dead. They thought they may have been kidnapped, instead.

The strange phone call and a missing ladder

Not long before the flames broke out in the Sodder home on Christmas Eve, 1945, Jennie Sodder answered the phone. A woman’s voice was on the line, and the woman asked for someone Jennie didn’t know so she assumed it was a wrong number. Jennie also said she heard the clinking of glasses and laughter in the background. The woman on the phone laughed strangely, Jennie said, but thinking nothing much of it, she hung up and went to bed.

Shortly afterward, Jennie woke again when something hit the roof and rolled. She went to sleep, but thirty minutes later, she was awakened, choking with smoke. George Sodder’s office was engulfed in flames, blocking the phone. George, Jennie, and four of the children escaped. Five Sodder kids were asleep in the attic and the fire blocked their escape, as well as George’s efforts to save them from inside the house.

Desperate, George tried everything he could to rescue his children, but their ladder was missing. George thought he might be able to reach the upper story if he pulled his trucks close and then stood on top of them, but they wouldn’t start. It was also later discovered that the Sodder phone line had been cut by a man who later admitted he stole block and tackle from their barn that night. And although neighbors called the fire department, help didn’t arrive until the next morning.

Possible cremation and beef liver

It was plausible that the five missing Sodder children’s remains were cremated in the heat of the blaze, explaining why more evidence was never found. George Sodder may have inadvertently trapped more heat when he bulldozed dirt over the charred remains, furthering the cremation process. But a witness later said, they, too, saw flaming objects strike the Sodder home, around the same time Jennie Sodder heard the bump on the roof and the rolling sound.

At the same time, a private detective hired by the Sodder family later interviewed Fayetteville Fire Chief F.J. Morris, who said he did find a human heart on-site, which he buried in a box. It was exhumed but it wasn’t a heart at all, it was beef liver, according to a Fayetteville funeral director. Then, four years later, the site of the Sodder home was excavated. A vertebrae turned up, but an expert declared it came from a male 16 to 22 years old, and not likely from Louis Sodder, who was 14 when he died.

Was it politcally-motivated arson?

George and Jennie Sodder were Italian immigrants, like many in the Fayetteville area, and when their house burned down, in December 1945, World War II had just recently ended. One possible motive for the arson could have been George’s strong stance against Benito Mussolini, the fascist Italian dictator. When George turned his coverage offer down, a life insurance salesman told him, ominously, that his house would burn, and that his children “would be destroyed” because of his political opinions.

All that, along with other evidence, led the Sodders to think their children didn’t die but were kidnapped, and they put up the billboard in 1952, offering money for more information. There were sightings reported of the Sodder children over the years, including strange letters, one including a picture of their son Louis, only older. “I love brother Frankie. Ilil boys. A90132 or 35,” was written on the back, like a secret code never deciphered. Another letter was from a woman in Houston who said that a man had confessed to her that he was Louis Sodder.

Around that same time, George drove to Texas to meet the man who said he was Louis and his brother Maurice, but when George arrived, the men changed their story and denied they were his sons. George died in 1969, never certain what happened to his children. Jennie died in 1989. Were the kids kidnapped over politics, or was it possibly the Italian mafia, instead, as some who have studied the story have alleged? Or is a tragic fire the best explanation for what killed the Sodder children?

It may never be known what happened that Christmas Eve in 1945. But about thirty years later, Jennie told the Charleston Daily Mail, “I’m going to fight this thing out and nothing is going to get me to give up hope that my children are still alive.”