One of the recurring themes of Barry since its first season premiere has been the idea that the mistakes people make in life, self-destructive behavior, and poor choices, are cyclical. In most TV shows, problem-solving is very linear; a person makes Mistake A, they apply Solution B, and they learn Life Lesson C, resetting to square one for the next episode so as not to break the formula. But Barry co-creator Alec Berg is not a sentimental writer, having made his bones on Seinfeld and Curb Your Enthusiasm, two shows that religiously adhered to Larry David’s dictum, “No hugging, no learning.”

And so, as we progress through season three, we find the same patterns popping up in the same characters. The trick will be to find who learns to break the cycle and who gets stuck.

Barry (Hader) tends to make his worst decisions out of a sense of love, as seen in season two when he decides to murder his girlfriend Sally’s (Goldberg) abusive ex-husband, Sam. Showing up at Sam’s hotel room, his plan is thwarted when he finds Sally there, confronting Sam in a scene which ends with Sam punching a wall, screaming at her, making her feel, once again, small and afraid.

The event is ultimately played for a laugh; terrible actor Barry overacts surprise when Sally later confesses to seeing her ex behind his back, and he only gets away with it because she’s too self-absorbed to ever see him for what he is. But the scene also makes a subtle point that finally gets addressed overtly this week; that Sally divorced one violent man capable of terrible things for another.

When Sally Reed was first introduced, the character was only ever defined in relation to the people around her. She was Barry’s love interest; she was Gene Cousineau’s (Winkler) acting student. It wasn’t until the end of season two that the character stopped reacting and began proactively making decisions. As Sally continues to develop as a fully-formed person, Goldberg continues to impress.

The episode opens with Barry having done a terrible thing out of his love for Gene. Taking to heart the idea that forgiveness is not given but earned, he has kidnapped his old acting teacher, stuffed him in his trunk, and is now driving him around Hollywood attempting to get him acting work.

When Sally has to tell Barry that Cousineau is radioactive in Hollywood, it ends badly in a scene that echoes exactly the hotel room scene with Sam. Barry has kept his violent side mostly hidden from his new friends since moving to LA, and a combination of being able to find release in his murder-for-hire business and the narcissism of the people around him have let Barry’s true nature go undetected.

This is the first time that Gene or Sally has seen the real Barry, and it’s terrifying. Gene knows now that Barry murdered his girlfriend and, in the wake of the event, he has managed to repair his relationship with his family and come to terms with the end of his dream of a successful acting career. For Gene, Barry represents a physical threat to the life he’s trying to rebuild. For Sally, he represents an existential threat to the role she’s been playing of a strong, successful woman who takes her destiny into her own hands while also playing a fictionalized version of that woman on a TV show.

Proof that Sally has grown as a person comes when Barry – in one of the series’ best recurring jokes, terrible actor Barry with no real interest in the business keeps accidentally impressing all the right people – tells her that he’s gotten a part on a hit show, and she’s capable of being genuinely happy for him.

In the meantime, Noho Hank’s (Carrigan) new relationship with would-be cartel leader Cristobal Sifuentes (Michael Irby) has given him something the character never had before – personal stakes. While Hank had become an integral part of the show over the past two seasons, there had been a low-key one-joke nature to his various arcs, and they mostly revolved around his feelings that veer between man-crush and hero-worship for the various more-successful criminals around him.

In this season, Anthony Carrigan has more heavy lifting to do as an actor, giving his character greater shade and depth of emotion. And he acquits himself perfectly, really finding within the sunny, optimistic Hank a full range of emotions, sometimes switching gears mid-scene with subtlety and artistry that is rare. A great thespian acts without ever drawing attention to what he’s doing, allowing the viewer to forget that he’s acting at all. Carrigan is doing the kind of work that puts him in a class with great character actors like John Cazale.

The question is whether this is good for the show, and the answer is less certain. Hank’s dramatic scenes with Cristobal are very dramatic, and the lack of humorous edge makes it stick out among Barry’s other scenes that more deftly mix black humor with action. There’s a balance to a show like Barry, and if a character or a B-plot throws off that balance it can be difficult to keep the series as a whole on track.

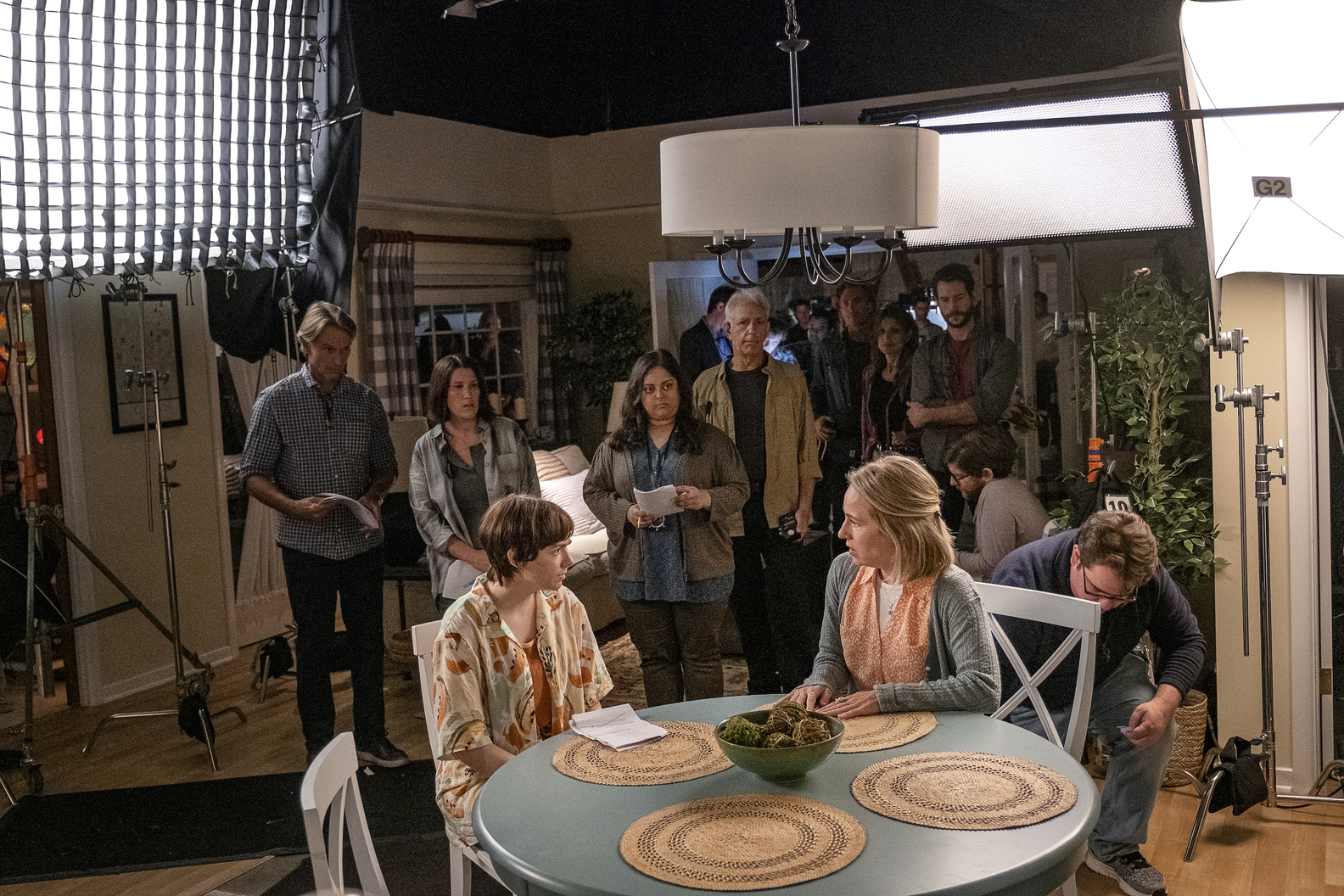

Bill Hader once again proves himself one of television’s bravest actors, turning in some career-best work with the show. In addition, he’s proving himself to be a director as consistent with getting the best performances from his cast as he is uneven with creating and maintaining a striking visual tone. A dramatic scene with Hank is staged, lit, and shot like a CW teen drama. I think somebody needs to confiscate Hader’s 100mm lens; there’s a late scene between Hader and Winkler that looks as if a first-year film student read an essay on Sergio Leone’s use of closeups and said, “I want to try that.”

Where Hader continues to excel as a director is in staging action and comedy. One of the great moves perfected by comedy team Zucker-Abrahams-Zucker was to stage outrageous physical comedy in the background while a serious scene plays out in the fore, and it’s a trick Hader manages to execute to great effect.

And on a final note, because I’ve been discussing the acting on Barry being top tier, the decision to have the real-life (and Emmy-winning!) casting director Allison Jones play a bumbling, funhouse mirror of herself is one of the series’ most inspired moves.

Top Honors

One of the recurring themes of Barry since its premiere has been the idea that the mistakes people make in life, the self-destructive behavior and poor choices, are cyclical. The trick will be to find who learns to break the karmic wheel, and who gets broken on it.

Barry