Warning: The following article contains spoilers for Attack on Titan and its ending.

More than a decade after its original debut, Attack on Titan finally came to an end today with an explosive series finale that ran for almost 90 minutes.

Manga readers had given us something of a warning, so we knew for months leading up to this fateful day that the ending would be controversial. Still, a part of me wanted to believe that perhaps Attack on Titan would be able to escape the tragic doom of unsatisfying conclusions that seem to afflict so many of our beloved stories these days. How terribly wrong I was.

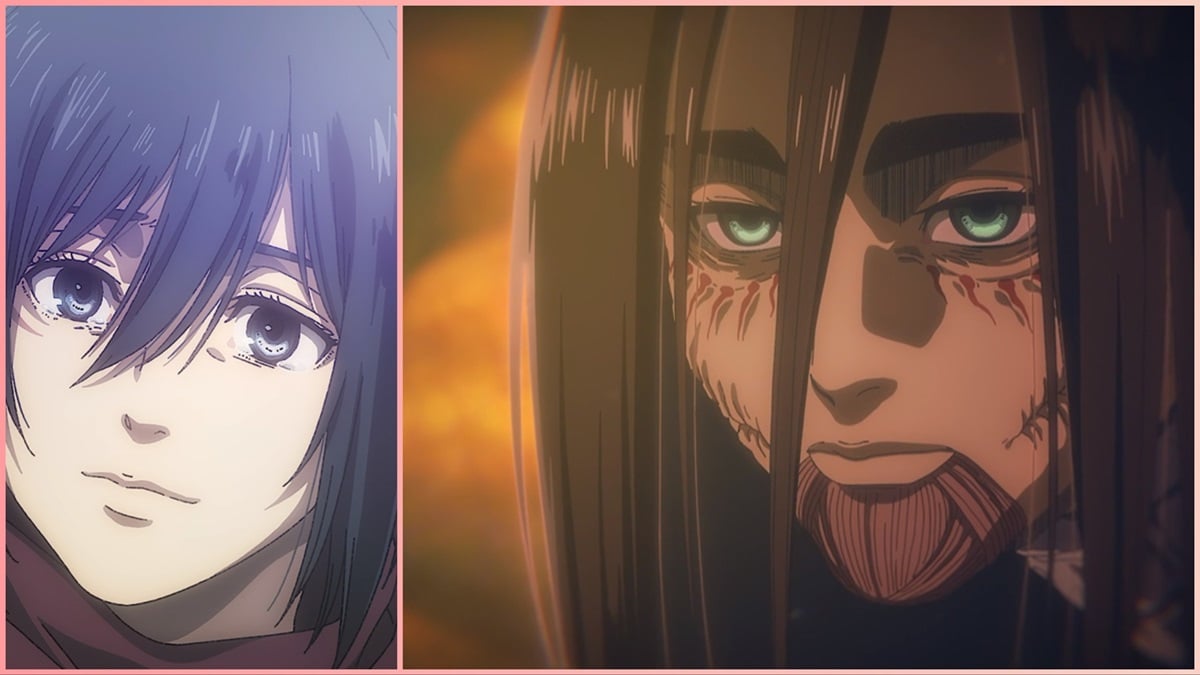

In the Attack on Titan series finale, the remaining heroes of Eldia and Marley band together to stop Eren from going through with the Rumbling. They finally manage to stop him just before he’s about to wipe out the remaining humans, whereupon we learn that the protagonist has already decimated 80% of the world’s population. The Survey Corps mount one final assault against Eren, and Mikasa manages to find him in person and detach his head from the Titan body, evidently killing him.

The protagonists are hailed heroes, but Paradis prepares for war under the influence of Yeagerists, with the story ending on the grim note that nothing has really changed and the cycle of violence will continue.

Now, barring the obvious bleak outlook — which has ever been creator Hajime Isayama’s signature storytelling style — this ending inspires a host of unanswered questions, ignores convenient plot developments, and doesn’t really give any resolution to the different character arcs. Which begs a serious question: What exactly was Isayama thinking?

Eren’s character resolution doesn’t work

Let’s start with the most glaring problem: Eren’s logic. If what we’re led to believe is true, our main character basically initiated the Rumbling as a ploy to bring out his friends, uniting them under one banner and painting them as the ultimate heroes when they eventually stopped him.

Eren wanted the rest of the world to view Eldians not as a threat, but as saviors. And the way he did that? By killing 80% of the people all around the globe, committing the very act that had fed the fires of contempt for generations; the same fear people had used as a wedge to justify all these years of cruel racial segregation.

For the sake of the argument, let’s assume that Eren wanted a definitive end to this conflict, which is why he refused to go forward with Armin’s original plan: that of incapacitating the rest of the world’s military so that their little island could catch up. In that case, even Isayama admits that Eren’s vision is flawed and that the return of war is inevitable at some point in the future.

What makes this more nonsensical is the fact that even Eren doesn’t know why he’s doing all of this. When confronted by Armin in those final moments, he claims to be doing this for his friends, but he later admits, paradoxically, that he just wanted a world devoid of any other person, where he could truly be free.

I think Hajime Isayama himself has realized over these past couple of years that his solution to Eren’s character doesn’t make sense. The conversation between Armin and Eren in the anime finale is different from the manga, and the explanation of a world free of other humans seems like a last-minute amendment to justify the climactic nature of having the Rumbling in the story — which, for that very reason, doesn’t work.

The story tries to somewhat rationalize all these developments by hinting that Eren may be mad, unable to distinguish between the past, present, and future because of the powers of his Attack and Founding Titans, but that could just be another plot device to rescue a narrative that’s in shambles.

The conflict in Attack on Titan always had a focal point. In those first seasons, it was the mystery of it all that propelled our characters forward: the burden of responsibility, the urge to break down walls of ignorance, the true nature of war. Now, in these last few outings, our protagonist has been lost inside his own brain, presiding over a hell of his own making that flies in the face of his character development.

Mikasa and Ymir are also problematic in their own way. Is the story somehow trying to imply that it was Mikasa’s sacrifice — her willingness to kill the one she loved — that inspired Ymir to let go after 2,000 years? The all-knowing god and founder of Eldians has been watching Mikasa, but she is hardly the first person in history to forsake their own feelings for the greater good of others.

Besides, there’s something incredibly absurd about the idea that a single act such as that, one that the characters had been indirectly attempting to do throughout the finale, managed to convince Ymir or give her the incentive to leave the world. Eren keeps insisting that it all hangs on Mikasa’s choice, and that has yet to be decided, but the story doesn’t even explain why that choice should be significant.

The more you think about the ending, the more it breaks down. At some point, Attack on Titan stopped being a great story with compelling characters and turned into a parade of moral dilemmas and layered symbolism for its viewers, somehow mistaking that for a convenient end to the story. The result is all too familiar to us by now: an ending that isn’t an ending, a climax that leaves the story in a gaping pit of unreached potential, and a character arc that crumbles beneath its own contradictions.

And so, like Isayama, I say goodbye to “the boy who sought freedom,” as much as it pains me to admit that the freedom was not the ideal of a burgeoning hero, but the contradictory, philosophical conundrum of an author who lost sight of the bigger picture somewhere along the way.